Techniques and tools to update your C# project - Migrating to nullable reference types - Part 4

Edit on GitHubPreviously, we saw how you can help the compiler’s flow analysis understand your code, by annotating your code for nullability.

In this final post of our series, we’ll have a look at the techniques and tools that are available to migrate to using nullable reference types in an existing code base.

In this series:

- Nullable reference types in C#

- Internals of C# nullable reference types

- Annotating your C# code

- Techniques and tools to update your project (this post)

Pick your approach: there is no silver bullet

As we have seen in a previous post, it can be an overwhelming experience to go all-in and enable the nullable annotation context for all projects in your solution.

Generally speaking, it’s a good idea to fully enable the nullable annotation context for new projects. This gets you the benefits of better static flow analysis from the start.

For existing projects, the choice is yours:

- For smaller projects, you can set

<Nullable>enable</Nullable>at the project level and plow through. - For larger projects, you may want to leave the project level set to

disable, and add#nullable enablefile by file. - Alternatively, you can set

warningsas the project level default, so you’ll see warnings where the compiler’s flow analysis infers potentialnullreferences. You can then add#nullable enablefile by file, and gradually add the right annotations and nullable attributes.

Regardless of the setting you choose at the project level, you’ll be in the mode of working through all warnings incrementally.

There is no silver bullet. There are, however, some techniques and tools that will help you reach the end goal of having a fully annotated codebase.

Start at the center and work outwards

Where to begin? What worked well for me on various code bases, was to start at the center.

Try and find the classes in your project that have zero dependencies on other reference types, apart from some strings. Data Transfer Objects (DTOs) / Plain-Old CLR Objects (POCOs) almost always fall under this category.

DTOs/POCOs are often used in many places throughout your project. Updating nullability for these classes means that nullability flows through the rest of your projects, and makes usages more reliable project-wide. So even if annotating one property seems like a small thing to do, it will flow through and be meaningful in the bigger picture.

Here’s an example:

public class LocationInfo

{

public string Country { get; set; }

public string Location { get; set; }

public LocationInfo(string country, string location)

{

Country = country;

Location = location;

}

}

This LocationInfo class only has two properties. Converting this class to using C# nullable reference types may be easy!

Add annotations or redesign your code

Let’s enable nullable reference types for this LocationInfo class!

- Add

#nullable enableto the class file - In the IDE, use Find Usages on every property, and determine if the properties are potentially set to

nullanywhere.- If there’s a value specified at every usage, keep the class as-is.

- If a

nullreference is passed in, you may need to annotate the property with?

- In the IDE, use Find Usages on the constructor, and determine if the constructor parameters are potentially set to

nullanywhere.

Going through usages, I found this particular case in my code base:

if (_databaseReader.TryCity(address, out var result) && result != null)

{

return new LocationInfo(

result.Country.Name,

result.City.Name);

}

I really want to recommend using ReSharper (R#) or JetBrains Rider once more. As mentioned before, both tools ship years of experience with nullable flow analysis, and it shows.

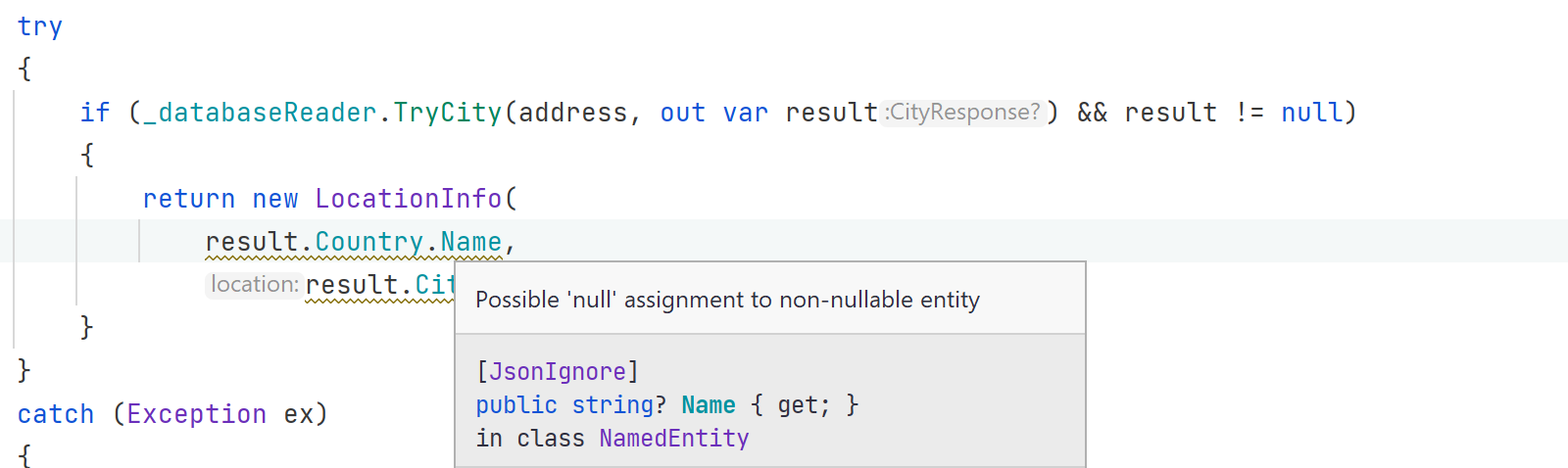

Both R# and Rider caught that result.Country.Name and result.City.Name may be null, even with the nullable warning context set to disabled at the project level:

This is one of those cases where you’ll have to decide on the approach to take…

- Should you annotate the

LocationInfoconstructor parameters? - Should you keep the

LocationInfoconstructor parameters as non-nullable and update the call site?

In this case there is only one call site that potentially passes a null reference, so let’s keep the LocationInfo constructor parameters non-nullable and update the call site instead:

if (_databaseReader.TryCity(address, out var result) &&

result != null &&

result.Country.Name != null &&

result.City.Name != null)

{

return new LocationInfo(

result.Country.Name,

result.City.Name);

}

return LocationInfo.Unknown;

The call site is updated with more thorough null checks, and a redesigned API:

- When no

nullvalues are present, we still returnLocationInfowith non-nullable properties. - When any values are

null, we returnLocationInfo.Unknown- a static property with both properties set to"Unknown". No need fornullchecks anywhereLocationInfois used, there’s always going to be a value.

Much like with async/await, nullable annotations will flow through your entire project. If we annotated the properties of LocationInfo as being nullable, we’d have to do null checks in our entire project. Instead, we chose to redesign our code and set a boundary of how far potential null references can flow. In this case, not far at all.

Once again, keep in mind there’s no silver bullet. In some cases, adding a nullable annotation will be the way to go, in other cases a small (or big) redesign may be better.

Don’t be afraid of null

Before we continue, there’s something important to keep in mind. The goal of migrating to C# nullable reference types, is to gain more confidence in the flow analysis provided by the compiler and the IDE. We’re not here to completely get rid of all null usages in our code!

As part of migrating to nullable reference types, you will be annotating some reference types with ?, sometimes you’ll be suppressing warnings with !, and sometimes, you’ll end up redesigning bits of your code.

Returning or passing around null is totally fine. Using C# nullable reference types and annotations makes doing so more reliable, with fewer chances of NullReferenceException being thrown unexpectedly. We’re building a safety net.

Nullable warning suppressions should be temporary

As part of migration, you may sprinkle some null-forgiving operators through your project’s code. When you’re not sure a reference type should be nullable or not, you can suffix the usage with the dammit-operator, !, and suppress any nullability warnings for that code path.

What’s nice about nullable warning suppressions, is that they disables flow analysis for a certain code path. You can use it to see the effect of what would happen to a code path if a reference that currently can be null would be redefined as non-nullable.

In some cases, you will indeed need to suppress null, and its usage is valid. In most cases, however, consider nullable warning suppressions a code smell. Using ! should be a temporary thing, use it with care. Since it disables flow analysis, it could hide nullability issues in your project - the exact issue you set out to improve upon!

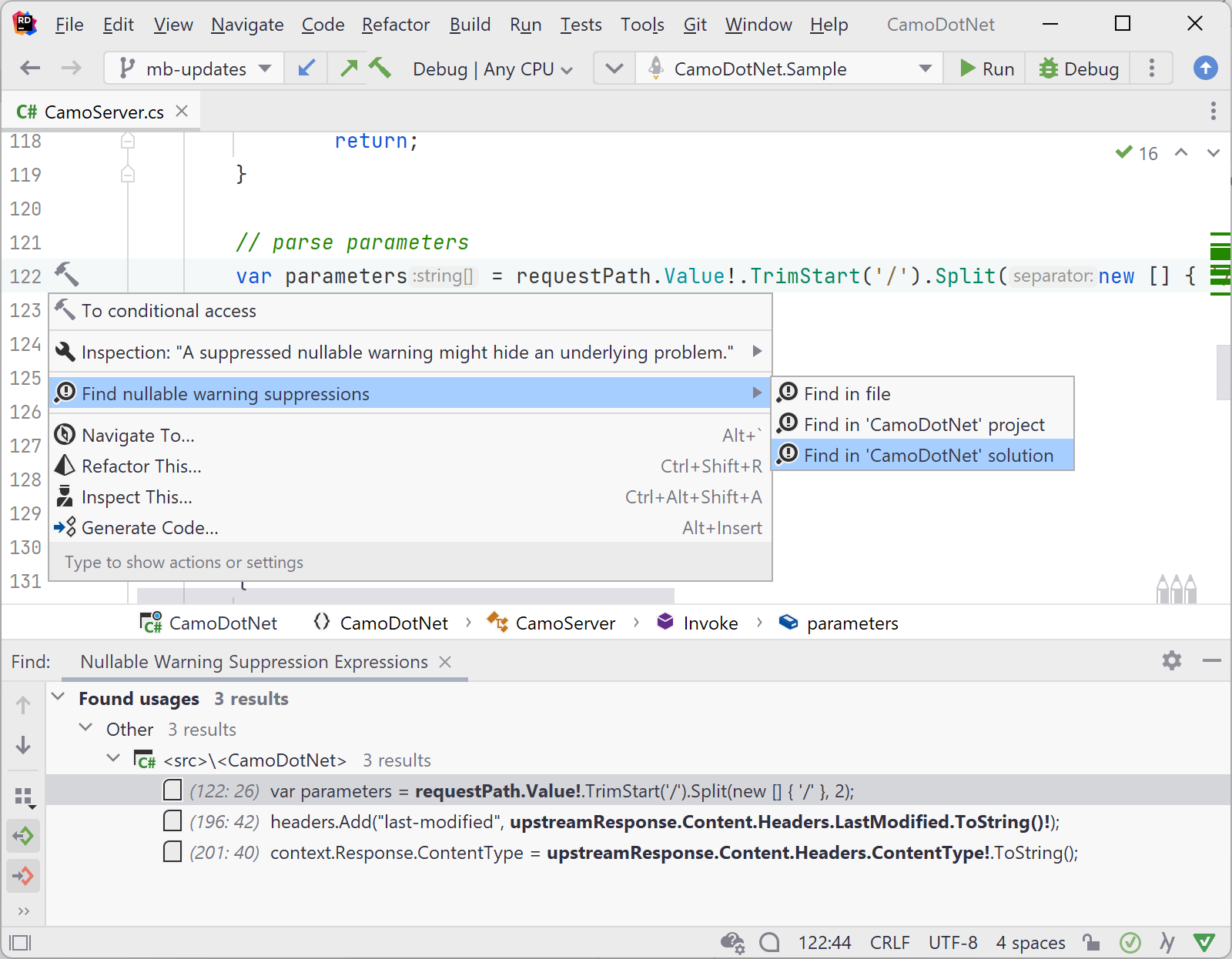

Tool tip: At any time during a migration, you can use ReSharper or JetBrains Rider to find all nullable warning suppressions. Use Alt+Enter on any suppression, and search for other suppressions in the current file, project, or solution.

Where is this value coming from? Where is it being used?

In many cases, Find Usages will be sufficient to get an idea of the direct usages of a class, constructor, method, or property. In other cases, you may need more information.

ReSharper (R#) and JetBrains Rider come with value tracking and call tracking to help you out here. Visual Studio 2022 also has a Track Value Source command, but your mileage with it will vary.

With value tracking, you can follow the entire flow of a specific value and determine where it is originating from and where it is being used.

Not sure if this TrackingAccount property should be annotated? The Inspect | Value Origin action will track all places where a value for this property can be assigned, and provides a tool window to jump to every location.

![]()

Note that it’s also possible to do the inverse, and analyze where the value from this TrackingAccount property is used.

JetBrains Annotations to C# nullable annotations

In a previous post, we discussed JetBrains Annotations already. If you’re working on a project where these annotations were already in use before C# introduced nullable reference types, you are in luck when migrating to C#’s version!

When you enable the nullable context, ReSharper and JetBrains Rider will help you with the migration. You’ll get hints on whether certain annotations are still needed.

#nullable enable

[NotNull]

private static string ReadColumnFromCsv(

CsvReader csv,

[CanBeNull] string columnName,

[NotNull] string defaultValue = "")

{

return !string.IsNullOrEmpty(columnName)

? csv[columnName]

: defaultValue;

}

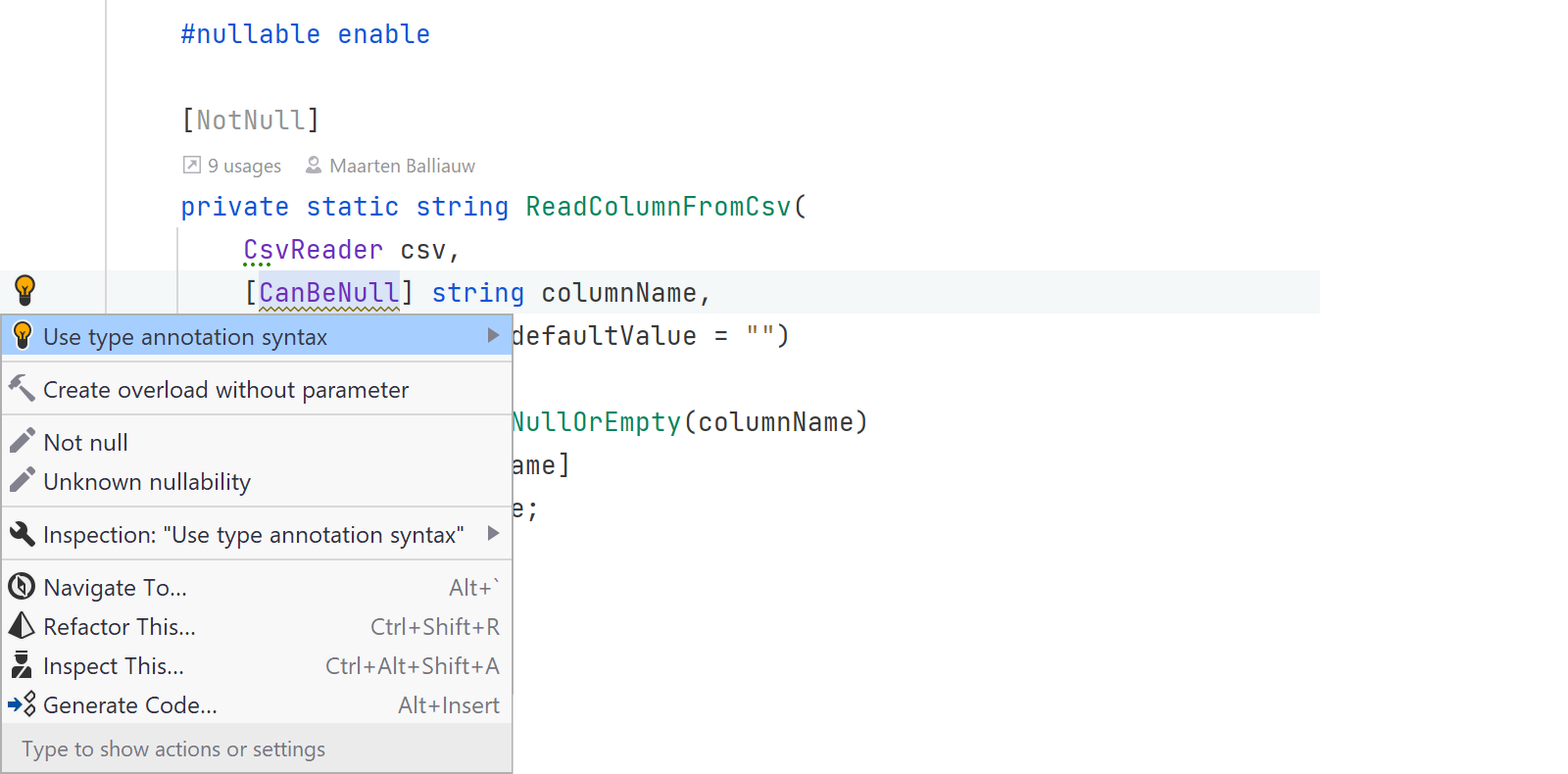

The ReadColumnFromCsv returns a non-nullable string, which means the [NotNull] annotation can be safely removed. The Remove redundant attribute quick fix is one Alt+Enter away!

Similarly, the [CanBeNull] string columnName parameter declaration can be updated. The original [CanBeNull] annotation can be removed, and converted to string? columnName.

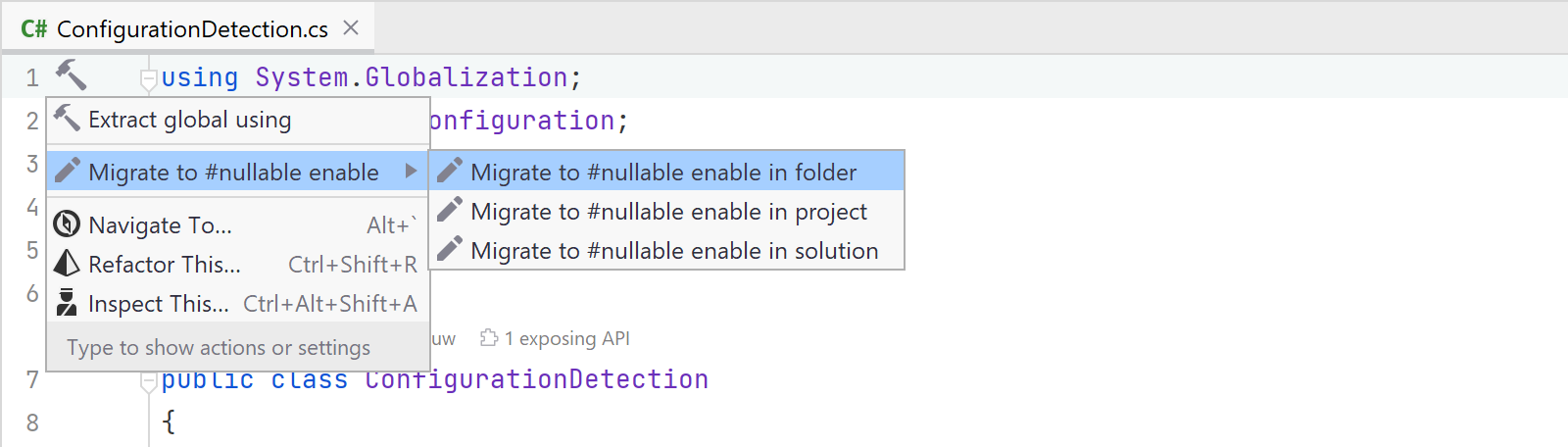

If you’re using the 2022.1 version of ReSharper or JetBrains Rider, there is a new Migrate to #nullable enable quick fix that does a few things at once:

- It inserts all

[NotNull]and[CanBeNull]attributes inherited from base members such as implemented interfaces. JetBrains annotations can be inherited (unlike C#’s annotations), so they are pulled in. - It infers annotations, by looking at your code’s branches. Are you returning

null? A nullable return type will be inferred. - It converts all JetBrains Annotations in the current file to C# annotations.

Tip: You can run most of these quick fixes on your entire file, project or solution in one go.

Determine nullability based on null checks

When you’re annotating your code, there are often clear hints in your code about what its nullability should be.

Here’s a quiz: in the following ReadColumnFromExcel method, what should the nullability of the columnName parameter be?

#nullable enable

public static string ReadColumnFromExcel(

Dictionary<int, string> data,

Dictionary<string, int> mappings,

string columnName,

string defaultValue = "")

{

if (columnName != null)

{

if (mappings.TryGetValue(columnName, out var columnIndex)

&& data.TryGetValue(columnIndex, out var columnData))

{

return columnData ?? defaultValue;

}

}

return defaultValue;

}

If you answered string? columnName, you are right!

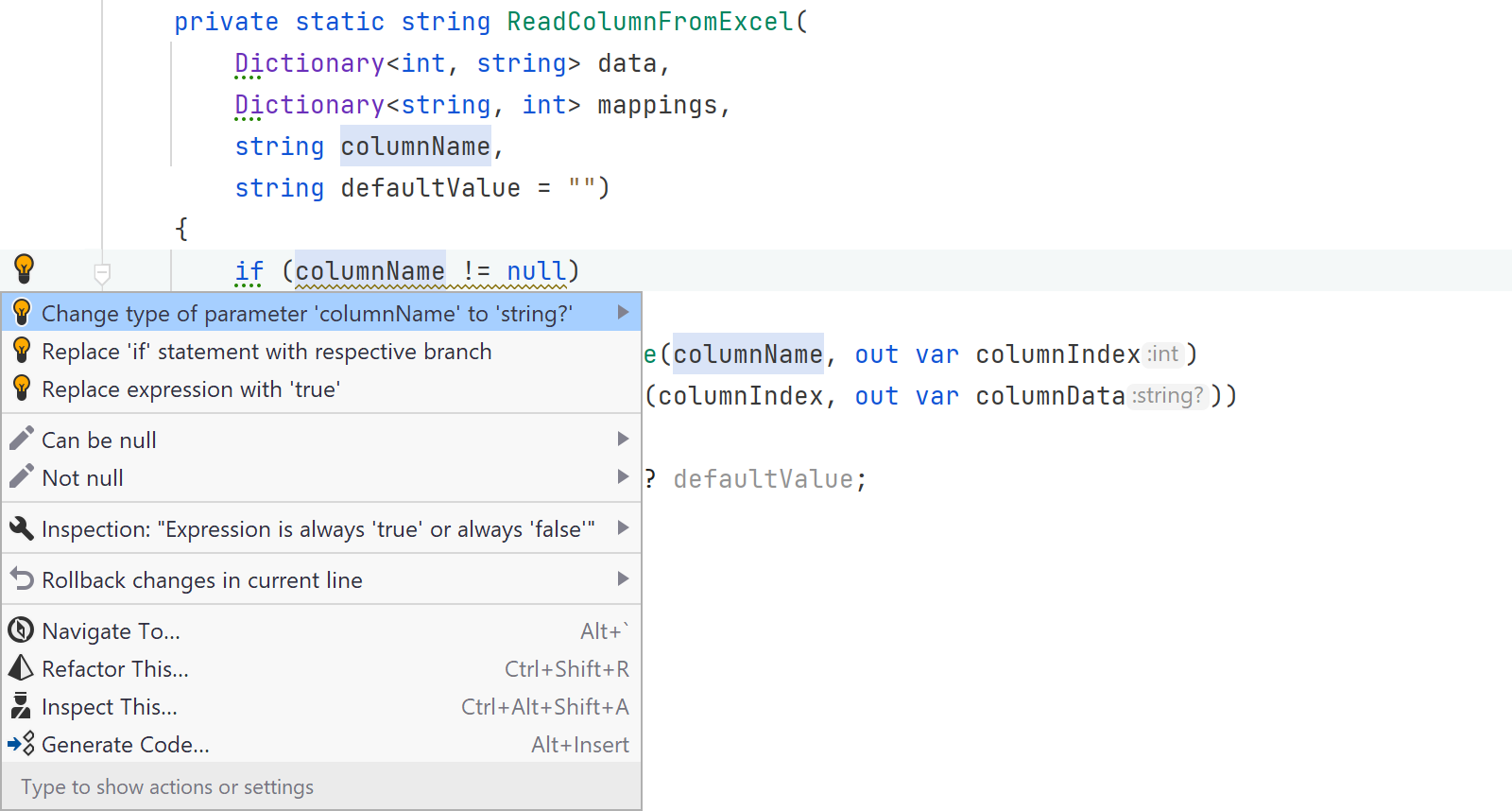

The first line of code in this method is checking if columnName != null, which means it should be annotated as nullable. There will be lots of these cases in the project you are migrating, and they usually provide a great hint in terms of annotating a parameter or property.

ReSharper and JetBrains Rider will detect these cases for you, and offer to fix the annotation(s) for you.

What about third-party libraries and external code?

When you are consuming third-party libraries, you’re in for a treat! Looking at the top downloaded packages on NuGet.org, not all of them are annotated. I’m sure if you look at the long tail of packages, there will be many more libraries that are not annotated at all!

Libraries with C# annotations

If you’re lucky, the library you are consuming has been fully annotated. There’s not much to say in this case: the C# compiler and all IDEs will pick up these annotations, and give you design- and compile-time hints. Great!

Libraries with JetBrains Annotations

If you’re consuming a library that ships its JetBrains Annotations, and you are using ReSharper or JetBrains Rider, you’re in luck as well.

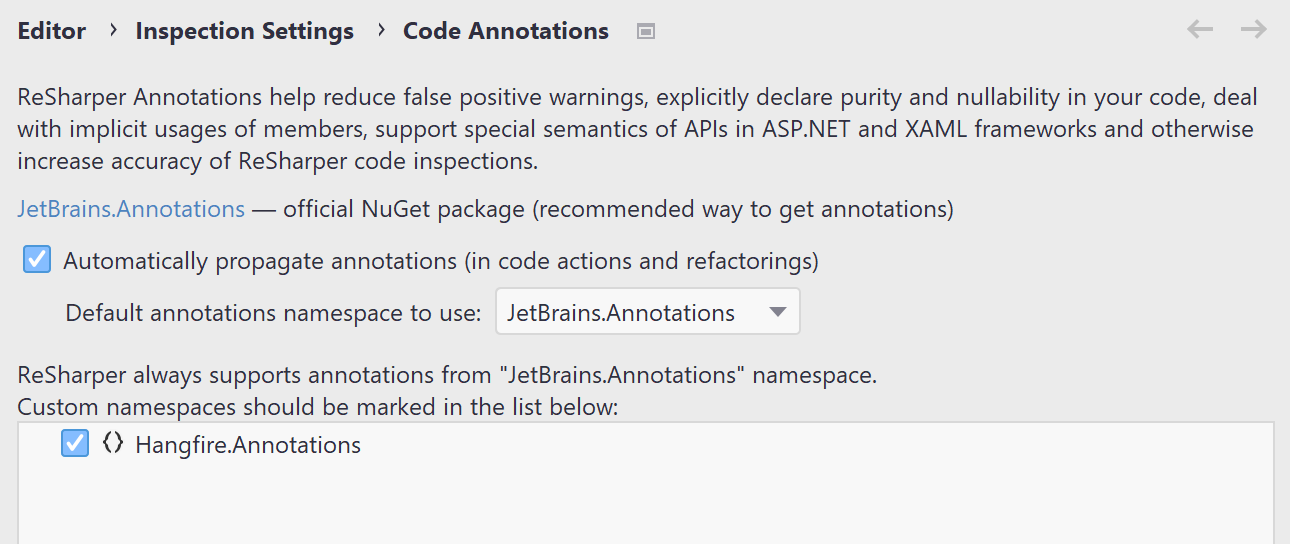

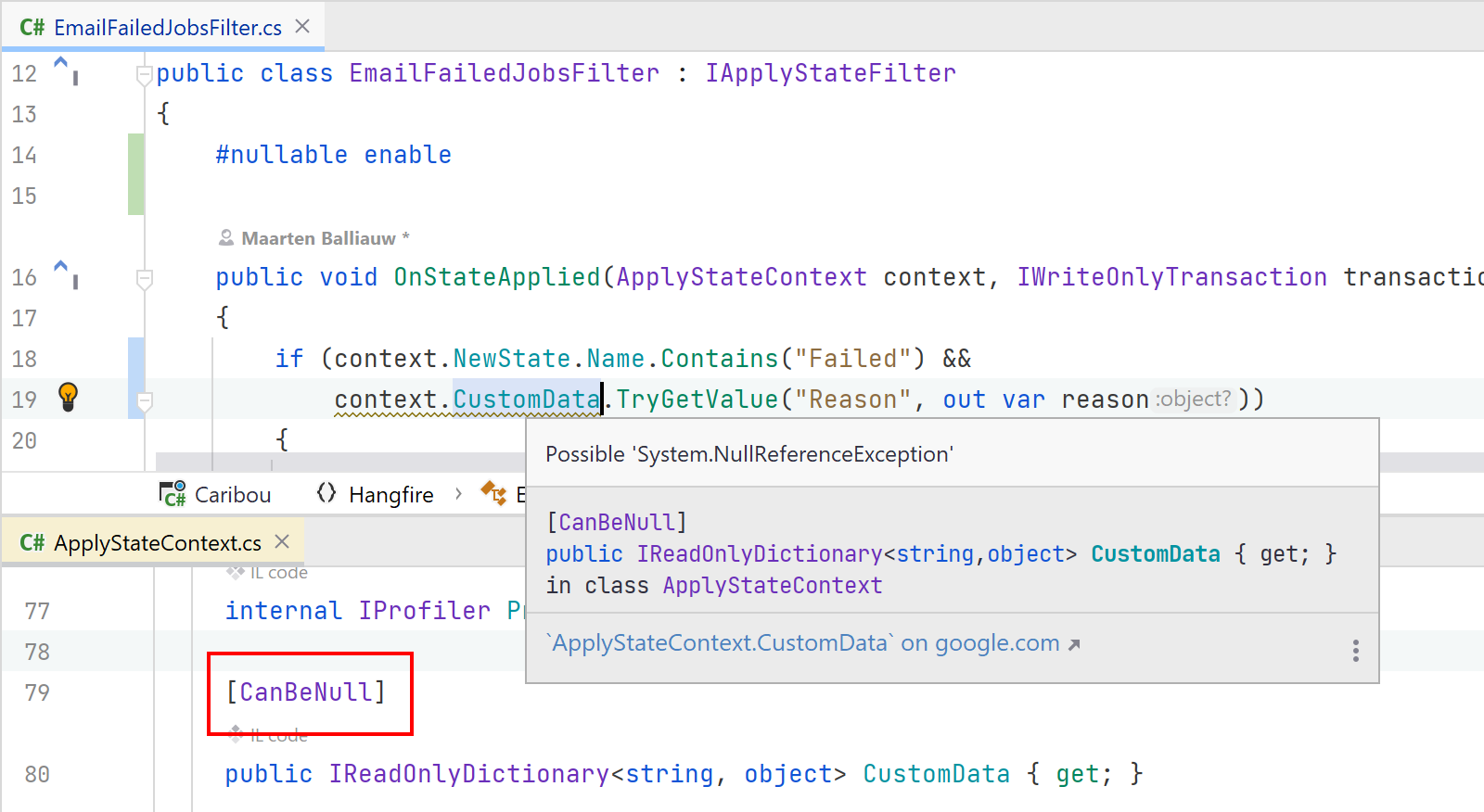

ReSharper and JetBrains Rider will automatically recognize annotations found in the JetBrains.Annotations namespace. Sometimes, libraries ship a custom namespace. The IDE will recognize these attributes, but you’ll still need to enable them in the settings.

Here’s an example with Hangfire. This project ships their annotations in the Hangfire.Annotations namespace:

After enabling it, the IDE considers the annotations in flow analysis:

While many libraries use JetBrains Annotations, not all of them ship them in their NuGet package.

Tip: If you have a library that is annotated with JetBrains annotations, make sure to ship them along with your code and make the life of many developers more enjoyable.

Libraries without annotations

If you are consuming libraries that are not annotated with either C#’s or JetBrains’ nullable annotations, you’ll have to do lots of null checks. Unless you dive into their source code, there is no way the compiler’s flow analysis can give you reliable hints.

If you’re using ReSharper or JetBrains Rider, you can enable pessimistic analysis to help uncover the places where you’ll need extra null checks.

Pessimistic analysis

By default, ReSharper and JetBrains Rider analyze your code in optimistic mode. In this mode, you will only see warnings about potentially dereferencing null if you explicitly checked it for null in the code path, or if it’s annotated as nullable.

The opposite mode is pessimistic. Unless a value is annotated as non-nullable, the IDE will expect you do a null check. The web help has more info about both modes.

Here’s an example. This ReadColumnFromCsv returns a non-null string. In pessimistic mode, you’ll see a warning when returning csv[columnName]. The CsvReader’s indexer has no nullable annotations, and therefore pessimistic analysis treats it as a potential null reference.

private static string ReadColumnFromCsv(

CsvReader csv,

string? columnName,

string defaultValue = "")

{

return !string.IsNullOrEmpty(columnName)

? csv[columnName] // Considered nullable in pessimistic mode

: defaultValue;

}

To get rid of this warning, you’ll have to return the defaultValue when csv[columnName] is null:

return !string.IsNullOrEmpty(columnName)

- ? csv[columnName]

+ ? csv[columnName] ?? defaultValue

: defaultValue;

Pessimistic analysis is not a mode I would recommend as the default in your projects. It’s more pessimistic than the compiler is!

It may be of help when migrating to C# nullable reference types, as it will definitely uncover some cases where you need additional null checks. Especially when working with third-party libraries that may not (yet) be annotated!

Deserializing JSON

If you have played with nullable reference types already, you may have found that there is no good way to get rid of all nullability warnings.

Typically, you will have several classes that will be used when deserializing JSON data, something like this:

public class User

{

[JsonProperty("name")]

public string Name { get; set; }

}

With C# nullable reference types enabled, a warning will be shown for the Name property: Non-nullable property is uninitialized. Consider declaring it as nullable.

Let’s look at how we can fix these warnings…

Make the property nullable - Bad!

Following the compiler’s advice, you can update the property and make it nullable:

public class User

{

[JsonProperty("name")]

public string? Name { get; set; }

}

Done! No more warnings! However, you now have to check for Name != null anywhere you consume this property…

Add a default value and suppress the warning - Bad!

Another option would be to suppress the warning, and change the User class to the following:

public class User

{

[JsonProperty("name")]

public string Name { get; set; } = default!;

}

Done! No more warnings! However, you are now lying to the compiler. When consuming the Name property, you may get a null reference after all.

Add a primary constructor (Newtonsoft.Json) - Good!

With Newtonsoft.Json, you can add a primary constructor that covers all properties of your class. The JSON deserializer will pick this up, and calls the constructor instead of setting the properties directly:

public class User

{

public User(string? name)

{

Name = name ?? "Unknown"; // or throw ArgumentNullException

}

[JsonProperty("name")]

public string Name { get; init; }

}

With this approach, you’ll get rid of nullability warnings without shooting yourself in the foot. If you don’t expect a null value from the JSON, stay close to that expectation and declare the property as non-nullable. In the constructor, you can set a default value, or throw an ArgumentNullException. Don’t blindly accept and propagate null.

Annotations and default values - Good!

Another approach to our problem would be setting a proper default value. In case no value is deserialized, and assuming the JSON deserializer doesn’t explicitly pass in null in such case, the property will be non-nullable and contain an expected default value:

public class User

{

[JsonProperty("name")]

public string Name { get; init; } = "Unknown";

}

This can also be accomplished using record classes, which is quite elegant for objects that are solely used for JSON deserialization:

public record User(

[property: JsonProperty("name")]

string Name = "Unknown"

);

An alternative would be to use a backing field, and make use of the [AllowNull] attribute that lets callers set null, while being certain that they will never get null when reading from this property.

public class User

{

private readonly string _name;

[AllowNull]

[JsonProperty("name")]

public string Name

{

get => _name;

init => _name = value ?? "Unknown";

}

}

Personally, I would not recommend this specific approach. It gets rid of all warnings, but it’s cumbersome to maintain with that backing field. And more importantly, since the [AllowNull] attribute works for the setter only, it can be confusing for consumers of your class.

To summarize, there are many solutions to making your JSON deserialization more reliable with C# nullable reference types. Whether you choose one of the approaches I have listed, or come up with another approach, don’t lie to the compiler, and don’t make life hard on yourself and your team by flowing potential null references around unnecessarily.

Remember that nullable warning suppressions are a code smell, and should be used with care - especially when you suppress warnings on values that are clearly null.

Be careful with Entity Framework

For most frameworks and libraries, nullable reference types and annotations are just hints to the IDE and compiler. That is, until you encounter a framework that uses the annotations for other things, such as Entity Framework.

From the documentation:

A property is considered optional if it is valid for it to contain

null. Ifnullis not a valid value to be assigned to a property then it is considered to be a required property. When mapping to a relational database schema, required properties are created as non-nullable columns, and optional properties are created as nullable columns.

In other words: if you update the nullability of an entity in C# code, a migration will be created that changes nullability in the database as well!

But what is considered “updating the nullability”? Adding or removing the nullable annotation (?) is one such change, and merely adding #nullable enable (or enabling nullability project-wide) is another.

In other words: if you enable nullability in a project or file, your database may change.

The Entity Framework documentation covers the various approaches to declaring entity properties and playing nice with C# nullable reference types.

Conclusion

In this final post of our series, we have covered various techniques and tools that are available to migrate your existing projects to use C# nullable reference types.

The benefit (and goal) of annotating your code, is that you get design-time and compile-time hints, from the IDE and the compiler. When adding annotations, steer clear of lying to the compiler. Suppressions are an anti-pattern in all but some cases. When needed, update the design of your API instead of passing around null values without there being a need , other than making a warning go away.

Thank you for reading!

P.S.: I realize this post was also a bit of a love letter for ReSharper (R#) and JetBrains Rider. Both tools are of great help when migrating and annotating your code.

If you have migrated (or are in the process of migrating), what tools are you using? What help do they offer? I would love to hear about those in the comments!

9 responses