Making string validation faster by not using a regular expression. A story.

Edit on GitHubA while back, we were performance profiling an application and noticed a big performance bottleneck while mapping objects using AutoMapper. Mapping is of course somewhat expensive, but the numbers we were seeing were way higher than expected: mapping was ridiculously slow! And “just mapping” was not a good explanation for these numbers. Trusting the work of Jimmy and trusting AutoMapper, we expected something else was probably causing this. And it was: a regular expression match was to blame!

The code was to blame

Actually not the regular expression itself, but the regular expression and the number of times it was called. While mapping, the target class’ Identifier property was obviously being set, and validating the incoming value using a regular expression.

Not a super big deal in itself, except that while mapping this validation was executed for a few thousand objects, resulting in around one second (sometimes more) to map these objects. Not a happy place!

Here’s the code that had the bottleneck:

private string _identifier;

public string Identifier

{

get

{

return _identifier;

}

set

{

if (Regex.IsMatch(value, "^[A-Za-z0-9@/._-]{1,254}$", RegexOptions.Compiled))

{

_identifier = value;

}

else

{

throw new InvalidPropertyValueException(nameof(Identifier), "The identifier is invalid.");

}

}

}

Aren’t regular expressions, especially those with RegexOptions.Compiled, supposed to be super fast? And especially in this case, where we’re only validating the string consists of a set of allowed characters, and making sure the string length is between 1 and 254 characters in length?

Some DuckDuckGo-ing (horrible as a verb…) later, we found a few interesting articles:

- Back in 2005, Jeff Atwood wrote about using

RegexOptions.Compiledand that it’s not always the best thing to use.RegexOptions.Compiledemits IL code and precompiles the regular expression, but that comes with a bit of a startup cost. It’s a tradeoff to make, and in our case we did expect this tradeoff to be one we could live with. Validation here happens quite a few times, so it makes sense to compile once and then reap the benefits later. - We read the excellent MSDN article “Best Practices for Regular Expressions in the .NET Framework”, describing common pitfalls in working with regular expressions and performance considerations. Make sure to read it, this is a really nice article about the Regex engine in .NET.

Unfortunately, none of these seemed to explain the numbers we were seeing. And doing the math on the number of calls times regex execution time, the regex was actually fast enough, the number of calls was the big issue…

So how could we make this faster? Trial and error! We decided to try a couple of solutions to the problem and benchmark them. But before we benchmark: let’s look at the solution candidates first.

Candidates for improvement

To be able to compare results, we decided on a baseline for our benchmark. This baseline would be:

Regex.IsMatch("Some.Sample-Data.To-Valid@te", "^[A-Za-z0-9@/._-]{1,254}$", RegexOptions.Compiled)

It is the same validation we found in production code, so let’s see if we can improve from there.

Candidate 1: don’t use RegexOptions.Compiled

Given RegexOptions.Compiled is considered to not always be the best option, we decided to do a non-compiled version as part of the benchmark:

Regex.IsMatch("Some.Sample-Data.To-Valid@te", "^[A-Za-z0-9@/._-]{1,254}$")

Our common sense told us this would not be better, but the only way to find out is by trying.

Candidate 2: using a Regex instance

While MSDN told us that regular expressions are cached when using Regex.IsMatch() and others, we decided to also try another option: creating an instance of Regex and using that one. Or, in code, we’d create one instance:

private static readonly Regex _precompiledRegex = new Regex("^[A-Za-z0-9@/._-]{1,254}$", RegexOptions.Compiled);

And then run the benchmark using:

_precompiledRegex.IsMatch("Some.Sample-Data.To-Valid@te");

Who knows, this could be better than our baseline!

Candidate 3: compiling the regular expression to an external assembly

This sounded interesting: instead of compiling the regular expression at run time, it’s also possible to use Regex.CompileToAssembly() and create an assembly that hold the precompiled regular expression.

Unfortunately, doing this comes with a little bit of extra work: we have to compile the assembly first. This, in itself, isn’t too hard, but it’s having to do the extra step. But anyway, here’s how:

var compilations = new []

{

new RegexCompilationInfo(

pattern: @"^[A-Za-z0-9@/._-]{1,254}$",

options: RegexOptions.Compiled,

name: "ValidationPattern",

fullnamespace: "RegexVsCode.Compiled",

ispublic: true)

};

Regex.CompileToAssembly(compilations,

new AssemblyName("RegexVsCode.Compiled, Version=1.0.0.0, Culture=neutral, PublicKeyToken=null"));

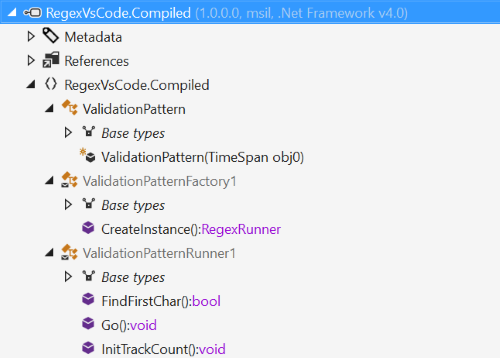

After running this, we can find a new assembly RegexVsCode.Compiled.dll in our bin folder, with a class ValidationPattern which holds our precompiled regular expression.

Always fascinated by the inner workings of things, I decided to open and decompile this generated assembly using dotPeek. Three classes seem to be generated:

A factory (used internally by the Regex engine), a ValidationPattern (as expected) and ValidationPatternRunner1 - the class that holds the regular expression logic. Don’t be scared, but this simple regex (again validating character classes + string length) does seem quite elaborate:

public override void Go()

{

string runtext = this.runtext;

int runtextstart = this.runtextstart;

int runtextbeg = this.runtextbeg;

int runtextend = this.runtextend;

int runtextpos = this.runtextpos;

int[] runtrack = this.runtrack;

int runtrackpos1 = this.runtrackpos;

int[] runstack = this.runstack;

int runstackpos = this.runstackpos;

this.CheckTimeout();

int num1;

runtrack[num1 = runtrackpos1 - 1] = runtextpos;

int num2;

runtrack[num2 = num1 - 1] = 0;

this.CheckTimeout();

int num3;

runstack[num3 = runstackpos - 1] = runtextpos;

int num4;

runtrack[num4 = num2 - 1] = 1;

this.CheckTimeout();

int end;

if (runtextpos <= runtextbeg)

{

this.CheckTimeout();

if (1 <= runtextend - runtextpos)

{

end = runtextpos + 1;

int num5 = 1;

while (RegexRunner.CharInClass(runtext[end - num5--], "\0\b\0-:@[_`a{"))

{

if (num5 <= 0)

{

this.CheckTimeout();

int num6 = runtextend - end;

int num7 = 253;

if (num6 >= num7)

num6 = 253;

int num8 = num6;

int num9 = 1;

int num10 = num6 + num9;

while (--num10 > 0)

{

if (!RegexRunner.CharInClass(runtext[end++], "\0\b\0-:@[_`a{"))

{

--end;

break;

}

}

if (num8 > num10)

{

int num11;

runtrack[num11 = num4 - 1] = num8 - num10 - 1;

int num12;

runtrack[num12 = num11 - 1] = end - 1;

runtrack[num4 = num12 - 1] = 2;

goto label_13;

}

else

goto label_13;

}

}

goto label_16;

}

else

goto label_16;

}

else

goto label_16;

label_13:

this.CheckTimeout();

int num13;

if (end >= runtextend - 1 && (end >= runtextend || (int) runtext[end] == 10))

{

this.CheckTimeout();

int[] numArray = runstack;

int index = num3;

int num5 = 1;

int num6 = index + num5;

int start = numArray[index];

this.Capture(0, start, end);

int num7;

runtrack[num7 = num4 - 1] = start;

runtrack[num13 = num7 - 1] = 3;

}

else

goto label_16;

label_15:

this.CheckTimeout();

this.runtextpos = end;

return;

label_16:

while (true)

{

this.runtrackpos = num4;

this.runstackpos = num3;

this.EnsureStorage();

int runtrackpos2 = this.runtrackpos;

num3 = this.runstackpos;

runtrack = this.runtrack;

runstack = this.runstack;

int[] numArray = runtrack;

int index = runtrackpos2;

int num5 = 1;

num4 = index + num5;

switch (numArray[index])

{

case 1:

this.CheckTimeout();

++num3;

continue;

case 2:

goto label_19;

case 3:

this.CheckTimeout();

runstack[--num3] = runtrack[num4++];

this.Uncapture();

continue;

default:

goto label_17;

}

}

label_17:

this.CheckTimeout();

int[] numArray1 = runtrack;

int index1 = num4;

int num14 = 1;

num13 = index1 + num14;

end = numArray1[index1];

goto label_15;

label_19:

this.CheckTimeout();

int[] numArray2 = runtrack;

int index2 = num4;

int num15 = 1;

int num16 = index2 + num15;

end = numArray2[index2];

int[] numArray3 = runtrack;

int index3 = num16;

int num17 = 1;

num4 = index3 + num17;

int num18 = numArray3[index3];

if (num18 > 0)

{

int num5;

runtrack[num5 = num4 - 1] = num18 - 1;

int num6;

runtrack[num6 = num5 - 1] = end - 1;

runtrack[num4 = num6 - 1] = 2;

goto label_13;

}

else

goto label_13;

}

There is not a lot of documentaton on this Go() method, but reading through it we can see a few things:

- It loops through the input string and checks various conditions

- It makes a number of cals to

this.CheckTimeout(), to verify the current processor tick count against a configured timeout tick count (so there are a few side-tracks in this code) - There are a few calls to

Capture()andUncapture(), the Regex-y stuff that keeps track of capture groups etc.

That’s… a lot of code to power a simple validation. But nevertheless: it’s all compiled, so performance may just be awesome!

Candidate 4: Custom code

Having seen the compiled code from candidate 3, we decided on writing our own valiation code without using regular expressions. We want to validate the string consists of a set of allowed characters, and making sure the string length is between 1 and 254 characters in length. No backtracking, no capturing, no nothing which the regular expression engine provides us. Just a boolean giving us a clue on whether the value is valid or not.

Our code?

private static bool Matches(string value)

{

var len = value.Length;

var matches = len >= 1 && len <= 254;

if (matches)

{

for (int i = 0; i < len; i++)

{

matches = char.IsLetterOrDigit(value[i])

|| value[i] == '@'

|| value[i] == '/'

|| value[i] == '.'

|| value[i] == '_'

|| value[i] == '-';

if (!matches) return false;

}

}

return matches;

}

Simple, readable. If the length is not ok, just return false. In other cases, check each character and when one does not match, return false early without validating the rest of the string. Looks good, easy to read.

Candidate 5: Custom code (just ASCII)

Edit - Some people pointed out in the comments that char.IsLetterOrDigit() works on Unicode and thus the custom code is not 100% similar to the original regular expression. They also pointed out performance could be better, so here’s an addition to the benchmark!

The char.IsLetterOrDigit() is already optimized a bit. It checks for the character class (latin or not) and then determines if it’s a letter or a digit base on the character class. That’s important: it checks the class, not the value! And turns out there are quite a few classes to loop trough.

So instead of using char.IsLetterOrDigit(), which checks on Unicode, let’s take the ASCII table at hand and manually check for character ranges instead.

Of course .NET is based on Unicode, but for the values from the ASCII character set the indexes in the character set match - so it’s safe to do this here.

The code:

private static bool MatchesASCII(string value)

{

var len = value.Length;

var matches = len >= 1 && len <= 254;

if (matches)

{

for (int i = 0; i < len; i++)

{

matches = (value[i] >= 48 && value[i] <= 57) // 0-9

|| (value[i] >= 65 && value[i] <= 90) // A-Z

|| (value[i] >= 97 && value[i] <= 122) // a-z

|| value[i] == '@'

|| value[i] == '/'

|| value[i] == '.'

|| value[i] == '_'

|| value[i] == '-';

if (!matches) return false;

}

}

return matches;

}

Still simple and readable. If the length is not ok, just return false. In other cases, check each character and when one does not match, return false early without validating the rest of the string. Let’s see how all candidates rank against each other…

Running the benchmark

I’d heard about BenchmarkDotNet before, but never had a good reason to try until now. BenchmarkDotNet makes it incredibly easy to write benchmarks and get results in a structured way. Go check their getting started with BenchmarkDotNet page - it takes a couple of attributes and a method call to run a reliable benchmark.

Our benchmark code

The benchmark we built was this one:

public class RegexVsCodeBenchmark

{

private static readonly Regex _precompiledRegex = new Regex("^[A-Za-z0-9@/._-]{1,254}$", RegexOptions.Compiled);

private static readonly ValidationPattern _assemblyCompiledRegex = new ValidationPattern();

private static bool Matches(string value)

{

// code from above candidate 4

}

private static bool MatchesASCII(string value)

{

// code from above candidate 5

}

[Benchmark(Description = "Regex.IsMatch - no options")]

public bool RegexMatch()

{

return Regex.IsMatch("Some.Sample-Data.To-Valid@te", "^[A-Za-z0-9@/._-]{1,254}$");

}

[Benchmark(Baseline = true, Description = "Regex.IsMatch - with RegexOptions.Compiled")]

public bool RegexCompiledMatch()

{

return Regex.IsMatch("Some.Sample-Data.To-Valid@te", "^[A-Za-z0-9@/._-]{1,254}$", RegexOptions.Compiled);

}

[Benchmark(Description = "Regex instance.IsMatch")]

public bool RegexPrecompiledMatch()

{

return _precompiledRegex.IsMatch("Some.Sample-Data.To-Valid@te");

}

[Benchmark(Description = "Assembly-compiled Regex instance.IsMatch")]

public bool RegexAssemblyCompiledMatch()

{

return _assemblyCompiledRegex.IsMatch("Some.Sample-Data.To-Valid@te");

}

[Benchmark(Description = "Custom code")]

public bool CustomCodeMatch()

{

return Matches("Some.Sample-Data.To-Valid@te");

}

[Benchmark(Description = "Custom code - ASCII only")]

public bool CustomCodeASCIIMatch()

{

return MatchesASCII("Some.Sample-Data.To-Valid@te");

}

}

We did a long run of this benchmark, to flatten out any compilation or optimization steps when starting the validations.

The results!

The results of our benchmark, run on my laptop:

BenchmarkDotNet=v0.10.3.0, OS=Microsoft Windows NT 6.2.9200.0

Processor=Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-4712HQ CPU 2.30GHz, ProcessorCount=8

Frequency=2240912 Hz, Resolution=446.2469 ns, Timer=TSC

[Host] : Clr 4.0.30319.42000, 32bit LegacyJIT-v4.6.1637.0

Clr : Clr 4.0.30319.42000, 32bit LegacyJIT-v4.6.1637.0

LongRun : Clr 4.0.30319.42000, 32bit LegacyJIT-v4.6.1637.0

RyuJitX64 : Clr 4.0.30319.42000, 64bit RyuJIT-v4.6.1637.0

Runtime=Clr

| Method | Job | Jit | Platform | Mean | StdErr | StdDev | Median | Scaled | Scaled-StdDev |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 'Regex.IsMatch - no options' | Clr | LegacyJit | X86 | 1,218.3968 ns | 11.8194 ns | 54.1633 ns | 1,217.1536 ns | 1.18 | 0.06 |

| 'Regex.IsMatch - with RegexOptions.Compiled' | Clr | LegacyJit | X86 | 1,031.7433 ns | 5.3394 ns | 20.6795 ns | 1,035.4243 ns | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| 'Regex instance.IsMatch' | Clr | LegacyJit | X86 | 700.5653 ns | 6.9606 ns | 41.1793 ns | 684.1019 ns | 0.68 | 0.04 |

| 'Assembly-compiled Regex instance.IsMatch' | Clr | LegacyJit | X86 | 661.8107 ns | 2.0592 ns | 7.9751 ns | 663.8463 ns | 0.64 | 0.01 |

| 'Custom code' | Clr | LegacyJit | X86 | 224.7163 ns | 0.7633 ns | 2.9562 ns | 224.3792 ns | 0.22 | 0.01 |

| 'Custom code - ASCII only' | Clr | LegacyJit | X86 | 64.3772 ns | 0.1642 ns | 0.6142 ns | 64.3874 ns | 0.06 | 0.00 |

| 'Regex.IsMatch - no options' | LongRun | LegacyJit | X86 | 1,198.7954 ns | 1.8423 ns | 30.8819 ns | 1,189.2547 ns | 1.12 | 0.03 |

| 'Regex.IsMatch - with RegexOptions.Compiled' | LongRun | LegacyJit | X86 | 1,068.7349 ns | 0.5691 ns | 9.3863 ns | 1,068.4618 ns | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| 'Regex instance.IsMatch' | LongRun | LegacyJit | X86 | 679.9538 ns | 1.3558 ns | 22.9687 ns | 678.8977 ns | 0.64 | 0.02 |

| 'Assembly-compiled Regex instance.IsMatch' | LongRun | LegacyJit | X86 | 669.3583 ns | 1.0979 ns | 18.5671 ns | 669.0480 ns | 0.63 | 0.02 |

| 'Custom code' | LongRun | LegacyJit | X86 | 213.6533 ns | 0.4295 ns | 7.1998 ns | 213.9596 ns | 0.20 | 0.01 |

| 'Custom code - ASCII only' | LongRun | LegacyJit | X86 | 64.9729 ns | 0.1251 ns | 2.1187 ns | 64.6303 ns | 0.06 | 0.00 |

| 'Regex.IsMatch - no options' | RyuJitX64 | RyuJit | X64 | 1,215.8591 ns | 11.9689 ns | 56.1390 ns | 1,223.4556 ns | 1.28 | 0.06 |

| 'Regex.IsMatch - with RegexOptions.Compiled' | RyuJitX64 | RyuJit | X64 | 947.7736 ns | 5.1000 ns | 19.0825 ns | 947.6938 ns | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| 'Regex instance.IsMatch' | RyuJitX64 | RyuJit | X64 | 604.0008 ns | 1.5033 ns | 5.8223 ns | 605.4844 ns | 0.64 | 0.01 |

| 'Assembly-compiled Regex instance.IsMatch' | RyuJitX64 | RyuJit | X64 | 622.9912 ns | 6.3879 ns | 33.8018 ns | 605.1827 ns | 0.66 | 0.04 |

| 'Custom code' | RyuJitX64 | RyuJit | X64 | 220.1304 ns | 1.0477 ns | 4.0575 ns | 218.1767 ns | 0.23 | 0.01 |

| 'Custom code - ASCII only' | RyuJitX64 | RyuJit | X64 | 51.4059 ns | 0.0785 ns | 0.2603 ns | 51.4702 ns | 0.05 | 0.00 |

First of all, there is no real difference between JIT versions. We sort of expected that but still wanted to see if there were any big changes in selecting the JIT version.

There are big differences in our different candidates, though. From slow to fast:

- Candidate 1,

Regex.IsMatch(not usingRegexOptions.Compiled) is clearly slowest. We expected this but still wanted to try. - The baseline,

Regex.IsMatch(usingRegexOptions.Compiled) isn’t significantly faster. It is faster, but the improvement is not spectacular. - Candidate 2, using an instance, only takes (roughly) 65% of the time our baseline takes. That’s significantly faster, and would be a good improvement in our codebase.

- Candidate 3, using a regular expression compiled into an external assembly, is only slightly faster than candidate 2. The difference could be in the startup time (where candidate 2 still has to be compiled at runtime), but we did not measure.

- Candidate 4, our custom code is fast! Our focused piece of code runs in 21% of the time the baseline took to run. That’s a massive improvement!

- Candidate 5, our custom code that checks just ASCII characters, seems to outperform all others. It runs in 6% of the time the baseline took to run. Nice!

Based on these result, our custom validation logic was added into production code and proved much, much faster!

Conclusion

Based on this post, you may think regular expressions are bad. In reality, they are not. They do seem to come with some considerations to make and some pitfalls you may encounter (see the articles linked higher up in this post), but they are great.

In the case at hand, though, custom code was the better path:

- The validation logic was simple, and writing it in code is still very readable

- We did not need capturing and all other features regular expressions give us

So then what is the takeaway for this post? I’d say there are three:

- Always be measuring. Use a profiler and regularly measure different code paths in an application. If anything looks out of expected ranges, look at how it can be improved.

- Always be learning. I had no idea

char.IsLetterOrDigit()would be “slow” compared with just checking ASCII characters. - Use regular expressions! Just not for validating string length.

Enjoy!

Edit - April 29, 2017 - Daniel Hegener took this a bit further and wrote another few alternative solutions that make string validation for the above case really fast. Go check it out!

20 responses