Rate limiting in web applications - Concepts and approaches

Edit on GitHubYour web application is running fine, and your users are behaving as expected. Life is good!

Is it, though…? Users are probably using your application in ways you did not expect. Crazy usage patterns resulting in more requests than expected, request bursts when users come back to the office after the weekend, and more!

These unexpected requests all pose a potential threat to the health of your web application and may impact other users or the service as a whole. Ideally, you want to put a bouncer at the door to do some filtering: limit the number of requests over a given timespan, limiting bandwidth, …

Last week, I covered how to use the ASP.NET Core rate limiting middleware in .NET 7.

In this post, let’s take a step back and explore the simple yet wide realm of rate limiting. We’ll go over how to decide which resources to limit, what these limits should be, and where to enforce these limits.

As a (mostly) .NET developer myself, I’ll use some examples and link some resources that use ASP.NET Core. The general concepts however will also apply to other platforms and web frameworks.

Introduction to rate limiting

Before we dive into the details, let’s start with an introduction about why you would want to apply rate limiting, and what it is.

Why rate limiting?

Let’s say you are building a web API that lets you store todo items. Nice and simple: a GET /api/todos that returns a list of todo items, and a POST /api/todos and PUT /api/todos/{id} that let you create and update a specific todo item. What could possibly go wrong with using these three endpoints?

Off the top of my head:

- The mobile app another team is building accidentally causes an infinite loop that keeps calling

POST, and tries to create a new todo item 10.000 times over the course of a few seconds before it crashes. That’s a lot of todo items in the database that should not be there. - You depend on an external system that throttles you for a number of requests. Frequent requests from one user to your API result in reaching that external limit, making your API unavailable for all your users.

- Someone is brute-forcing the

GETmethod, trying to get todo items for all your users. You have security in place, so they will never get in without valid credentials, but your database has to run a query to check credentials 10 times per second. That’s rough on this small 0.5 vCPU database instance that seemed good on paper. - An aggressive search engine spider accidentally adding 20.000 items into a shopping cart that is stored in memory.

There are probably more things that could go wrong, but you get the picture. You, your team, or external factors may behave in ways you did not expect.

That profile picture upload that usually gets small images uploaded? Guaranteed someone will try to upload a 500MB picture of the universe at some point.

When you build an application, there’s a very real chance that you don’t know how it will be used, and what potential abuse may look like. You are sharing CPU, memory and database usage among your users. One bad actor, whether intentional or accidental, can break or make your application slow, spoiling the experience for other users.

What is rate limiting?

Rate limiting, or request throttling, is an approach to reduce the fall-out of unexpected or unwanted traffic patterns to your application.

Typically, web applications implement rate limiting by setting an allowance on the number of requests for a given timeframe. If you are a streaming service, you may want to limit the outgoing bandwidth per user over a given time. Up to you!

The ultimate goal of imposing rate limits is to reduce or even eliminate traffic and usage of your application that is potentially damaging. Regardless of the traffic being accidental or malicious.

What should I rate limit?

I will give you a quote that you can use in other places:

Rate limit everything.

– Maarten Balliauw

With everything, I mean every endpoint that uses resources that could slow down or break your application when exhausted or stressed.

Typically, you’ll want to rate limit endpoints that make use of the CPU, memory, disk I/O, the database, external APIs, and the likes.

Huh. That does mean everything, even your internal (health) endpoints! You’ll want to prevent resource exhaustion, and make usage of shared resources more fair to all your users.

Naive rate limiting

The title of this section already hints at it: don’t use the approach described in this section, but do read through it to get into the mindset of what we are trying to accomplish…

If you wanted to add rate limiting to your ASP.NET Core web application, how would you do it?

Most probably, you will end up with a solution along these lines:

- Add a database table

Events, with three columns:UserIdentifier– who do we limitActionIdentifier– what do we limitWhen– event timestamp so we can apply a query

- Implement a request delegate to handle rate limits

The request delegate could look something like the following, storing events and then counting the number of events over a period of time:

app.Use(async (http, next) =>

{

var eventsContext = app.Services.GetRequiredService<EventsContext>();

// Determine identifier

var userIdentifier = http.User.Identity?.IsAuthenticated == true

? http.User.Identity.Name!

: "anonymous";

// Determine action

var actionIdentifier = http.Request.Path.ToString();

// Store current request

eventsContext.Events.Add(new Event

{

UserIdentifier = userIdentifier,

ActionIdentifier = actionIdentifier,

When = referenceTime

});

await eventsContext.SaveChangesAsync();

// Check if we are rate limited (5 requests per 5 seconds)

var referenceTime = DateTime.UtcNow;

var periodStart = referenceTime.AddSeconds(-5);

var numberOfEvents = eventsContext.Events

.Count(e => e.UserIdentifier == userIdentifier && e.ActionIdentifier == actionIdentifier && e.When >= periodStart);

// Rate limited - respond 429 status code

if (numberOfEvents > 5)

{

http.Response.StatusCode = 429;

return;

}

// Not rate limited

await next.Invoke();

});

That should be it, right? RIGHT?!?

Well… Let’s start with the good. This would be very flexible in defining various limits and combinations of limits. It’s just code, and the logic is up to you!

However, every request is at least 2 queries to handle potential rate limiting. The Events table will grow. And fast! So you will need to remove events at some point.

The database server will suffer at scale. Imposing rate limits to protect shared resources, has now increased the load on this shared resource!

Ideally, the measurements and logic for your rate limiting solution should not add this additional load. A simple counter per user identifier and action identifier should be sufficient.

Rate limiting algorithms

Luckily for us, smart people have thought long and hard about the topic of rate limiting, and came up with a number of rate limiting algorithms.

Quantized buckets / Fixed window limit

An easy algorithm for rate limiting, is using quantized buckets, also known as fixed window limits. In short, the idea is that you keep a counter for a specific time window, and apply limits based on that.

An example would be to allow “100 requests per minute” to a given resource. Using a simple function, you can get the same identifier for a specific period of time:

public string GetBucketName(string operation, TimeSpan timespan)

{

var bucket = Math.Floor(

DateTime.UtcNow.Ticks / timespan.TotalMilliseconds / 10000);

return $"{operation}_{bucket}";

}

Console.WriteLine(GetBucketName("someaction", TimeSpan.FromMinutes(10)));

// someaction_106062120 <-- this will be the key for +/- 10 minutes

You could keep the generated bucket name + counter in a dictionary, and increment the counter for every request. based on the counter, you can then apply the rate limit. When a new time window begins, a new bucket name is generated and the counter can start from 0.

This bucket name + counter can be stored in a C# dictionary, or as a named value on Redis that you can easily increment (and expires after a specific time so Redis does the housekeeping for you).

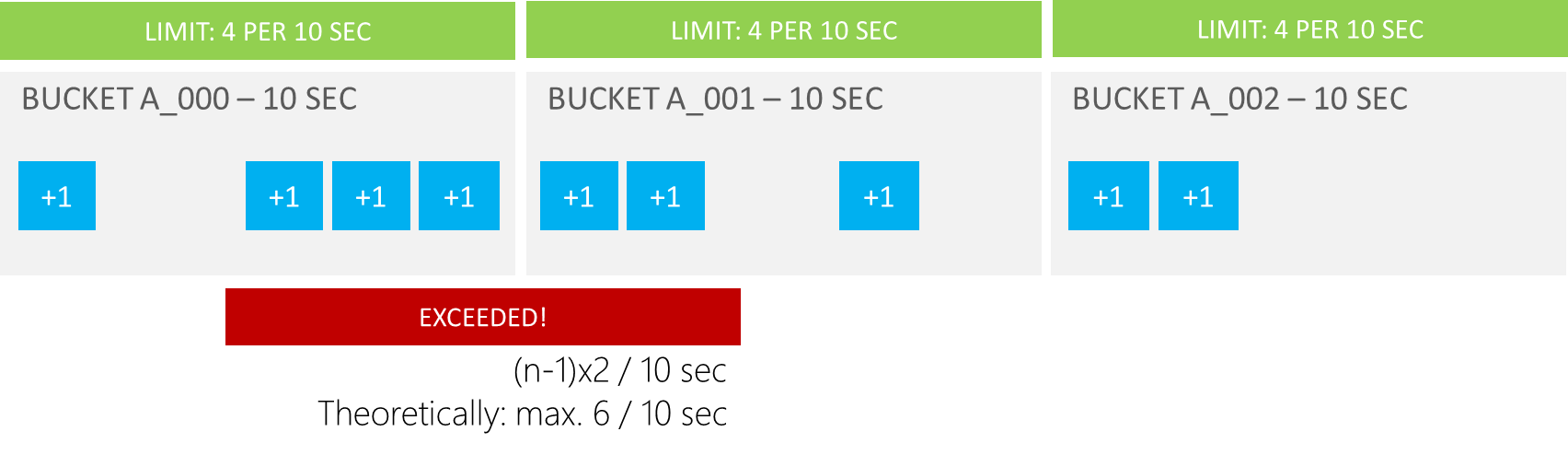

There is a drawback to quantized buckets / fixed window limits… They are not entirely accurate.

Let’s say you want to allow “4 requests per 10 seconds”. Per 10-second window, you allow only 4 requests. If all of those requests come in at the end of the previous window and the start of the current window, there’s a good chance the expected limit is going to be exceeded.

The limit of 4 requests is true per fixed window, but not per sliding window…

Does this matter? As always, “it depends”.

If you want to really lock things down and don’t want to tolerate a potential overrun, then yes, this matters. If your goal is to impose rate limits to prevent accidental or intentional excessive resource usage, perhaps this potential overrun does not matter.

In the case where you do need a sliding window limit, you could look into sliding window limit approaches. These usually combine multiple smaller fixed windows under the hood, to reduce the chance of overrunning the imposed limits.

Token buckets

Widely used in telecommunications to deal with bandwidth usage and bandwidth bursts, are token buckets. Token buckets control flow rate, and they are called buckets because buckets and water are a great analogy!

“Imagine a bucket where water is poured in at the top and leaks from the bottom. If the rate at which water is poured in exceeds the rate at which it leaks water out, the bucket overflows and no new requests can be handled until there’s capacity in the bucket again.”

If you don’t like water, you could use tokens instead:

“Imagine you have a bucket that’s completely filled with tokens. When a request comes in, you take a token out of the bucket. After a predetermined amount of time, new tokens are added to the bucket. If you take tokens out faster than they are added, the bucket will be empty at some point, and no new requests can be handled until new tokens are added.”

In code, this could look like the following. The GetCallsLeft() method returns how many tokens are left in the bucket.

public int GetCallsLeft() {

if (_tokens < _capacity) {

var referenceTime = DateTime.UtcNow;

var delta = (int)((referenceTime - _lastRefill).Ticks / _interval.Ticks);

if (delta > 0) {

_tokens = Math.Min(_capacity, _tokens + (delta * _capacity));

_lastRefill = referenceTime;

}

}

return _tokens;

}

One benefit of token buckets is that they don’t suffer the issue we saw with quantized buckets. If too many requests come in, the bucket overflows (or is empty if you prefer the water analogy) and requests are limited.

Another benefit is that they allow bursts in traffic: if your bucket allows for 60 tokens per minute (replenished every second), clients can still burst up to 60 requests for the duration of 1 second, and thereafter the flow rate becomes 1 request per second (because of this replenishment flow).

There are other variations of the algorithms we have seen, but generally speaking they will correspond to either quantized buckets or token buckets.

Deciding rate limits

Now that we have seen the basic concepts of rate limiting, let’s have a look at the decisions to be made before implementing rate limiting in your applications.

Which resources to rate limit?

Deciding which resources to rate limit is easy. Here’s a quote from a famous blog author:

Rate limit everything.

– Maarten Balliauw

Your application typically employs a “time-sharing model”. Much like a time-sharing vacation property, you don’t want your guests to be hindered by other guests, and ideally come up with a fair model that allows everyone to use the vacation property in a fair way.

Rate limiting should be applied to every endpoint that uses resources that could slow down or break your application when exhausted or stressed. Given every request uses at least the CPU and memory of your server, and potentially also disk I/O, the database, external APIs and more, you’ll want to apply rate limiting to every endpoint.

What are sensible limits?

Deciding on sensible limits is hard, and the only good answer here is to measure what typical usage looks like.

Measurement brings knowledge! A good approach to decide on sensible limits is to:

- Find out the current # of requests for a certain resource in your application.

- Implement rate limiting, but don’t block requests yet. When a limit is hit, log it. This will let you fine-tune the numbers.

- Iterate on measurements and logs, and when you are certain you know what the limit should be, start enforcing it.

As an extra tip, make sure to constantly monitor rate limiting events, and adjust when needed. Perhaps a newer version of your mobile app makes more requests to your API, and this is expected traffic.

Too strict limits will annoy your users. Remember, you don’t want to police the number of requests. You want fair usage of resources. You don’t call the police when two toddlers fight over a toy. If they both need the toy, maybe it’s fine to have multiple toys or have them play at different times, so they don’t have to fight over it.

Will you allow bursts or not?

Depending on your application and endpoint, having one rate limit in place will be enough. For example, a global rate limit of 600 requests per minute may be perfect for every endpoint in your application.

However, sometimes you may want to allow bursts. For example, when your mobile app starts, it performs some initial requests in rapid succession to get the latest data from your API, and after that it slows down.

To handle these bursts, you may want to implement a “laddering” approach, and have multiple different limits in place:

| Limit | Operation A | Operation B | Operation C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Per second | 10 | 10 | 100 |

| Per minute | 60 | 60 | 500 |

| Per hour | 3600 | 600 | 500 |

In the above table, a client could make 10 requests per second to Operation A. 10 per second would normally translate to 36000 request per hour, but maybe at the hourly level, only 3600 is a better number.

Again, measure, and don’t prematurely add laddering. There’s a good chance a single limit for all endpoints in your application may be sufficient.

What will be the partition/identifier?

Previously, we used a user identifier + action/operation identifier to impose rate limits. There are many other request properties you can use to partition your requests:

- Partition per endpoint

- Partition per IP address

- Keep in mind users may be sharing an IP address, e.g. when behind a NAT/CGNAT/proxy

- Partition per user

- Keep in mind you may have anonymous users, how will you distinguish those?

- Partition per session

- What if your user starts a new session for every request?

- What if your user makes use of multiple devices with separate sessions?

- Partition per browser

- Partition per header (e.g.

X-Api-Token), …

Also here, “it depends” on your application. A global rate limit per IP address may work for your application. More complex applications may need a combination of these, e.g. per-endpoint rate limiting combined with the current user.

Decide on exceptions

Should rate limiting apply to all requests? Well… yes! We already discussed all endpoints in your application should be rate limited.

A better question would be whether the same limits should apply for all types of users. As usual, the answer to this question will depend on your application. There is no silver bullet, but here are some examples to think about.

Good candidates to have different rate limits in place:

- Your automated monitoring - the last thing you want is nightly PagerDuty alerts because of your monitoring system being rate limited.

- Counter point: maybe you do want to have a rate limit in place, so your monitoring can check rate limits are enabled?

- Your admin/support team - your support team may make a lot of requests to your application to help out users, so it’s best to not get in their way.

- Counter point: maybe a rate limit does make sense, so a disgruntled employee can’t go and scrape lots of data or add swear words into lots of places with an automated script.

- Web crawlers - your marketing folks won’t be happy if your app is not visible in search engines!

- Counter point: there are aggressive crawlers, and you also don’t want them to get in the way of your users. There are some

robots.txtentries many spiders respect, but a rate limit could be needed.

- Counter point: there are aggressive crawlers, and you also don’t want them to get in the way of your users. There are some

- “Datacenter IP ranges” - If you have a mobile app targeted at consumers, does traffic coming from AWS, Azure and other big hosters make sense? If you expect mostly “residential” and mobile traffic, perhaps you can reduce automated traffic from other sources with a more strict rate limit. There’s a list of datacenter IP ranges that you can use for this.

- Counter point: VPN providers out there are often going to be in these IP ranges. Legitimate users may use datacenter IP addresses in those cases. Also at the time of writing, my dad’s Starlink subscription runs over what looks like a Google Compute Engine IP address.

An additional exception could be certain groups of customers. If your API is your product, it could be part of your business model to allow e.g. users of your “premium plan” to have different limits.

Also here, measuring will help you make an informed decision. If you see excess traffic from web crawlers, a tighter rate limit may be needed. If you see your support folks unable to help users, maybe a less strict rate limit for them makes more sense.

Responding to limits

What should happen when a request is being rate limited? You could “black hole” the request and silently abort it, but it’s much nicer to communicate what is happening, and why.

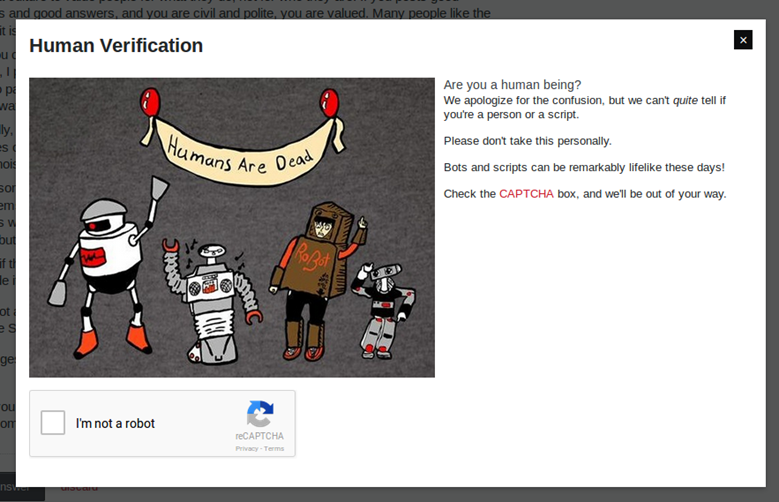

One example I like is StackOverflow. When using their website and posting responses to many questions in rapid succession, there’s a good chance their rate limiter may ask you to prove you are human:

This is pretty slick. Potential issues with a broken application posting multiple answers rapidly are avoided by rate limiting. Potential scripts and bots will also be rate limited, and their service happily hums along.

Another good example is GitHub. First of all, they document their rate limits so that you can account for these limits in any app you may be building that uses their API. Second, any request you make will get a response with information about how many requests are remaining, and when more will be available:

$ curl -I https://api.github.com/users/octocat

> HTTP/2 200

> Date: Mon, 01 Jul 2013 17:27:06 GMT

> x-ratelimit-limit: 60

> x-ratelimit-remaining: 56

> x-ratelimit-used: 4

> x-ratelimit-reset: 1372700873

In addition, when a rate limit is exceeded, you’ll get a response that says what happened and why, and where to find more information.

> HTTP/2 403

> Date: Tue, 20 Aug 2013 14:50:41 GMT

> x-ratelimit-limit: 60

> x-ratelimit-remaining: 0

> x-ratelimit-used: 60

> x-ratelimit-reset: 1377013266

> {

> "message": "API rate limit exceeded for xxx.xxx.xxx.xxx. (But here's the good news: Authenticated requests get a higher rate limit. Check out the documentation for more details.)",

> "documentation_url": "https://docs.github.com/rest/overview/resources-in-the-rest-api#rate-limiting"

> }

If you have mixed types of users, you could inspect the Accept header and return different responses based on whether text/html is requested (likely a browser) and when application/json is requested (likely an API client).

Other services have documented their limits as well. For example, NuGet lists limits for each endpoint and also shows you what the response would look like when a limit is reached.

Try and always communicate why a client is being limited, and when to retry. A link to the documentation may be enough.

This is of course not mandatory, but if you’re offering an API to your users, it does help in providing a great developer experience.

429, 403, 503, … status codes

From the GitHub example, you may have seen the status code returned when rate limits are exceeded is

403(Forbidden). Other services return a503(Service unavailable), and others return a429status code (Too Many Requests).There’s no strict rule here, but it does look like many services out there follow a convention of using

429 Too Many Requests.Regarding the specific headers being returned, an IETF draft “RateLimit Fields for HTTP” is in the works.

Where to store rate limit data and counters?

When you search for information about rate limiting, there’s a good chance you’ll come across questions about where to store rate limit data and counters. More than once, you’ll see questions related to using your database, Redis or other distributed cached.

Keep it simple. Do you really need 100% accurate counters that all instances of your application share? Or is it enough to apply “10-ish requests per second per user” on every instance of your application and be done with it?

If your rate limit is part of your revenue model, for example when you sell API access with specific resource guarantees, then you’ll probably want to look into shared and accurate counters. When your goal is to ensure fair use of shared resources in your application, storing counters per instance may be more than enough.

Where to apply rate limiting?

In an ideal world, the consumer of your application would know about rate limits and apply them there, before even attempting a request. This would mean your server and application will never even have to process the request.

Unfortunately, we’re not living in an ideal world, and clients will send requests to your application. How far will you let traffic flow?

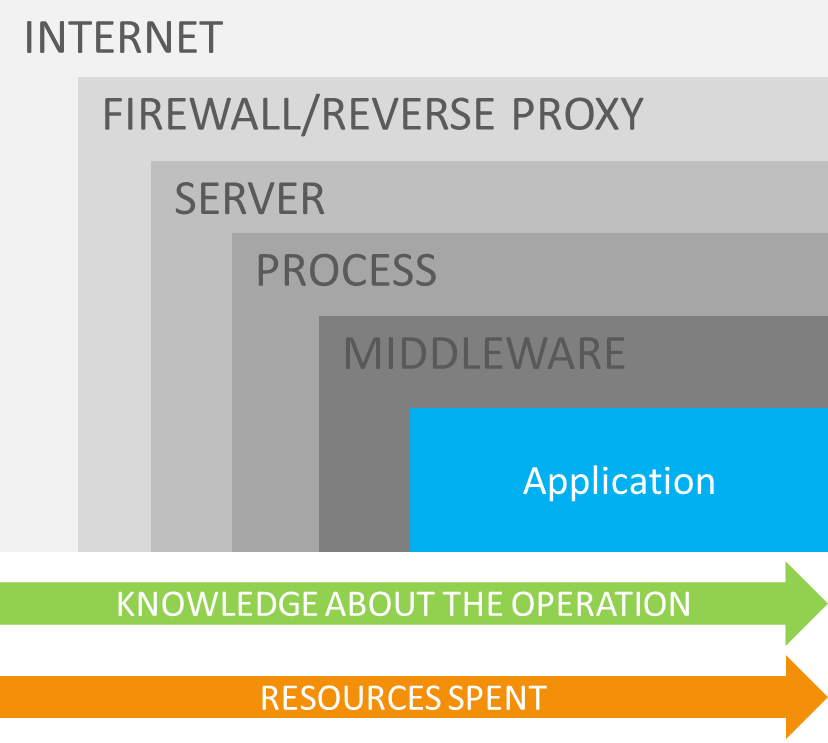

If you think of web-based applications (including APIs and the likes), there are several places where rate limits could be applied.

Maybe you are using a Content Delivery Network (CDN) that acts as a reverse proxy for your application, and they can rate limit? Or perhaps the framework you are using has some rate limiting infrastructure that can be used?

The closer to your application you add rate limiting, the more knowledge you will have about the user. If your partitioning requires deep knowledge about user privileges etc., your application may be the only place where rate limiting can be applied.

When you partition based on IP address and the Authentication header, a CDN or reverse proxy could handle rate limiting as they don’t need extra data for every request.

The closer to your application you add rate limiting, the more resources will be spent. If you’re running a serverless application and rate limit on a CDN or reverse proxy, you won’t be billed for execution of your serverless function. If you need more information about the user, then your serverless function may need to apply rate limiting (but also costs money).

Depending on what makes sense for your application, here are some resources:

- In your application

- Stefan Prodan’s AspNetCoreRateLimit (highly recommend, it has lots of options for every aspect discussed in this blog post)

- ASP.NET Core Rate Limiting middleware in .NET 7

- Reverse proxy

- Content Delivery Network / API Gateway

Monitoring and circuit breakers

Applications change, usage patterns change, and as such, rate limits will also need to change. Perhaps your rules are too strict and hurting your users more than your application resources. Perhaps the latest deployment introduced a bug that is making excess calls to an API, and this needs to be fixed?

Keep an eye on your rate limiting, keep track of who gets rate limited, when and why. Use custom metrics to build dashboards on # of rate limiting actions kicking in to help during incident troubleshooting.

Also make sure you can adapt quickly if needed, by having circuit breakers in place. If with a new deployment all of your users experience rate limiting for some reason, having an emergency switch to just turn off rate limits will be welcome. Perhaps on/off is too coarse, and your circuit breaker could be in making rate limits dynamic and allowing for updates using a configuration file.

Wrapping up

Whether intentional or accidental, users of your application will bring along unexpected usage patterns. Excess requests, request bursts, automated scripts, brute-force requests - all of these are going to happen at some point.

These types of usage may pose a potential threat to your application’s health, and one abusive user could impact several others. Your application runs on shared resources, and ideally you want them to be shared in a fair manner.

This is where rate limiting comes in, and I hope I was able to give you a comprehensive overview of all the things you can and have to consider when implementing a rate limiting solution.

The concept of “it depends” definitely applies when building a rate limiting solution. Small and simple may be enough, and many of the considerations in this post will only apply for larger applications. But do consider to “rate limit everything” to make resource sharing more fair.

0 responses