Techniques for real-time client-server communication on the web (SignalR to the rescue)

Edit on GitHub When building web applications, you often face the fact that HTTP, the foundation of the web, is a request/response protocol. A client issues a request, a server handles this request and sends back a response. All the time, with no relation between the first request and subsequent requests. Also, since it’s request-based, there is no way to send messages from the server to the client without having the client create a request first.

When building web applications, you often face the fact that HTTP, the foundation of the web, is a request/response protocol. A client issues a request, a server handles this request and sends back a response. All the time, with no relation between the first request and subsequent requests. Also, since it’s request-based, there is no way to send messages from the server to the client without having the client create a request first.

Today users expect that in their projects, sorry, “experiences”, a form of “real time” is available. Questions like “I want this stock ticker to update whenever the price changes” or “I want to view real-time GPS locations of my vehicles on this map”. Or even better: experiences where people collaborate often require live notifications and changes in the browser so that whenever a user triggers a task or event, the other users collaborating immediately are notified. Think Google Spreadsheets where you can work together. Think Facebook chat. Think Twitter where new messages automatically appear. Think your apps with a sprinkle of real-time sauce.

How would you implement this?

But what if the server wants to communicate with the client?

Over the years, web developers have been very inventive working around the request/response nature of the web. Two techniques are being used on different platforms and provide a relatively easy workaround to the “problem” of HTTP’s paradigm where the client initiates any connection: simple polling using Ajax and a variant of that, long polling.

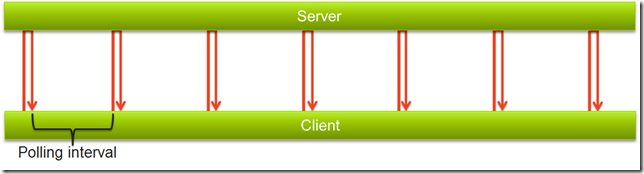

Simple Ajax polling is, well, simple: the client “polls” the server via an Ajax request the server answers if there is data. The client waits for a while and goes through this process again. Schematically, this would be the following:

A problem with this is that the server still relies on the client initiating the connection. Whenever during the polling interval the server has data for the client, this data can only be sent to the client when the next polling cycle occurs. This is probably no problem when the polling interval is in the 100ms range, apart from the fact that you’ll be hammering your servers when doing that. From the moment your polling interval goes up to say 2 seconds or even 30 seconds, you lose part of the “real time” communication idea.

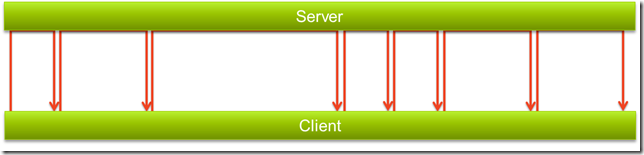

This problem has been solved by using a technique called “long polling”. The idea is that the client opens an Ajax-based connection to the server, the server does not reply until it has data. The client just has the false feeling that the request is taking a while, and eventually will have some data coming back from the server. Whenever data is returned, the client immediately opens up a “long polling” connection again. Schematically:

There’s no polling interval: as long as the connection is open, the server has the ability to send data back to the client. Awesome, right? Not really… Your servers will not be hammered with billions of requests, but the requests it handles will take a while to complete (the “long poll”). Imagine what your ASP.NET thread pool will do in such case… Well, unless you implement your server-side using an IAsyncHttpHandler or similar. Otherwise, your servers will simply stop accepting requests.

HTML5 to the rescue?

As we’ve seen, both techniques that exist work to simulate full-duplex communication between client and server. However, both of them have some disadvantages if you don’t know what you are doing. Also, the techniques described before are just simulating bi-directional communication. Wouldn’t it be nice to have a solution that works great and was intended to do this? Meet HTML5 WebSockets.

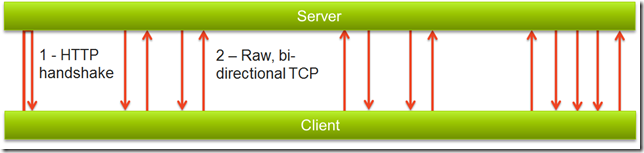

WebSockets offer a real, bi-directional TCP connection between the client and the server. That’s right, a TCP (non-HTTP) connection. To establish a WebSocket connection, the client sends a WebSocket handshake request over HTTP, the server sends a WebSocket handshake response with details on how to open the actual TCP connection. Easy as that! Schematically:

Unfortunately, the web does not evolve that fast… WebSockets are still a draft specification (“CTP” or “alpha” as you will). Not all browsers support them. And because they are using a raw TCP connection, many proxy servers used at companies don’t support them, yet. We’ll get there, just not today. Also, if you want to use WebSockets with ASP.NET, you’ll be forced to use the preview release of .NET 4.5.

So what to do in this messed up world? How to achieve real-time, bi-directional communication over the interwebs, today?

SignalR to the rescue!

SignalR is “an asynchronous signaling library for ASP.NET that Microsoft is working on to help build real-time multi-user web applications”. Let me rephrase that: SignalR is an ASP.NET library which leverages the three techniques I described before to create a seamless experience between client and server.

The main idea of SignalR is that the boundary between client and server should become easier to tackle. A really quick example would be two parts of code. The client side:

1 var helloConnection = $.connection.hello; 2 3 helloConnection.sayHelloToMe = function (message) { 4 alert(message); 5 }; 6 7 $.connection.hub.start(function() { 8 helloConnection.sayHelloToAll("Hello all!"); 9 });

The server side:

1 public class Hello : Hub { 2 public void SayHelloToAll(string message) { 3 Clients.sayHelloToMe(message); 4 } 5 }

Are you already seeing the link? The JavaScript client calls the C# method “SayHelloToAll” as if it were a JavaScript function. The C# side calls all of its clients (meaning the 200.000 browser windows connecting to this service :-)) JavaScript method “sayHelloToMe” as if it were a C# method.

If I add that not only JavaScript clients are supported but also Windows Phone, Silverlight and plain .NET, does this sound of interest? If I add that SignalR can use any of the three techniques described earlier in this post based on what the client and the server support, without you even having to care… does this sound of interest? If the answer is yes, stay tuned for some follow up posts…

This is an imported post. It was imported from my old blog using an automated tool and may contain formatting errors and/or broken images.

One response